There’s a myth about Reggie Jackson that most of the controversy and conflict in his career took place during his five seasons with the Yankees. That’s really not the case. While his battles of ego with Billy Martin and George Steinbrenner garnered the most media attention of his career, Jackson was just as controversial during his days in Oakland. He butted heads with manager Dick Williams and most of his coaching staff. He once fought Billy North, a onetime friend who had become a mortal enemy by 1974. Jackson frequently sparred with A’s owner/general manager Charlie Finley, who could make Boss Steinbrenner look like Charles Ingalls by comparison. One of Jackson’s controversial episodes bordered on silliness, but it was just the kind of occurrence that made life with Finley’s A’s so entertaining.

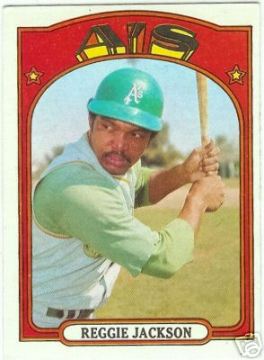

In 1972, Jackson, reported to Oakland’s spring training camp in Arizona replete with a fully-grown mustache (as seen in his 1972 Topps card, No. 435), the origins of which had begun to sprout during the 1971 American League Championship Series. To the surprise of his teammates, Jackson had used part of his off-season to allow the mustache to reach a fuller bloom. In addition, Jackson bragged to teammates that he would not only wear the mustache, but possibly a beard, come Opening Day.

Such pronouncements would have hardly created a ripple in today’s game. Players freely make bold fashion statements with mustaches and goatees, and routinely wear previously disdained accessories like earrings. It’s really no big deal in 2007. But this was 1972, still a conservative time within the sport, in stark contrast to the rebellious attitudes of younger generations throughout the country. Given that no major league player had been documented wearing a mustache in the regular season since Wally Schang of the Philadelphia A’s in 1914, Jackson’s pronouncements made major news in 1972.

In the post-Schang era, several players had donned mustaches during spring training, including Stanley "Frenchy" Bordagaray of the Brooklyn Dodgers in the mid-1930s and, more recently, Richie Allen of the St. Louis Cardinals and Clete Boyer of the Atlanta Braves in the first two years of the seventies. (Allen’s 1971 Topps card shows the mustache in clear view, but it’s believed that the Dodger Stadium photograph was taken just before the start of the season.) Yet, in each case, the player had shaved off the mustache by Opening Day, either by his own volition or because of a mandate from the team. After all, there existed an unwritten rule within the conservative sport, one that strongly frowned upon facial hair. In addition, several individual teams had more recently instituted their own formal policies (most notably the Cincinnati Reds in the 1960s), policies that forbade their players from sporting facial hair.

Baseball’s conservative grooming standards, which had been in place for over 50 years, were now being threatened by one of the game’s most visible players. Not surprisingly, Jackson’s mustachioed look quickly cornered the attention of Charlie Finley and Dick Williams. "The story as I remember it," says former A’s first baseman Mike Hegan, "was that Reggie came into spring training… with a mustache, and Charlie didn’t like it. So he told Dick to tell Reggie to shave it off. And Dick told Reggie to shave it off, and Reggie told Dick what to do. This got to be a real sticking point, and so I guess Charlie and Dick had a meeting, and they said well, ‘Reggie’s an individual so maybe we can try some reverse psychology here.’ Charlie told a couple of other guys, I don’t know whether it was [Dave] Duncan, or Sal [Bando], or a few other guys to start growing a mustache. Then, [Finley figured that if] a couple of other guys did it, Reggie would shave his off, and you know, everything would be OK."

According to A’s captain Sal Bando, Finley wanted to avoid having a direct confrontation with Jackson over the mustache. For one of the few times in his tenure as A’s owner, Finley showed a preference for a subtle, more indirect approach. "Finley, to my knowledge," says Bando, "did not want to go tell Reggie to shave it. So he thought it would be better to have all of us grow mustaches. That way, Reggie wouldn’t be an ‘individual’ [anymore]." Rollie Fingers, Catfish Hunter, Darold Knowles, and Bob Locker followed Reggie’s lead, each sprouting his own mustache. Instead of making Jackson feel less individualistic, thus prompting him to adopt his previously clean-shaven look, the strategy had a reverse and unexpected effect on Finley.

"Well, as it turned out, guys started growing ‘em, and Charlie began to like it," says Hegan in recalling the origins of baseball’s "Mustache Gang." Finley offered a cash incentive to any player who had successfully grown a mustache by Father’s Day. "So then we all had to grow mustaches," says Hegan, "and that’s how all that started. By the time we got to the [regular] season, almost everybody had mustaches." Even Dick Williams, known for his military brush-cut and clean-shaven look during his managerial tenure in Boston, would join the facial brigade by growing a patchy, scraggly mustache of his own. Baseball’s longstanding hairless trend had officially come to an end.

And as always, Finley had found a way to profit from it.

Merry Christmas, everybody!

Bruce Markusen, who writes Cooperstown Confidential for MLB.com, is the author of the upcoming book, Out of Left Field: Unusual Characters in Baseball History.