What to eat at Yankee Stadium according to Eater.

[Photo Credit: Eat a Duck]

Ivan Solotaroff spent much of the summer of 1988 hanging out in the bleachers at Yankee Stadium. It was a different time: The Bronx wasn’t hospitable to, well, anyone back then. This was before the Disneyfication of Manhattan, before Rudy Giuliani, before Brooklyn became a Mecca of gentrification. You could go to Yankee Stadium and buy a ticket almost any night, then go smoke a joint in all but the fanciest of box seats. It could be an unnerving place, but it was not without its charms, which Solotaroff captures in “The Regulars: 1,900 Years in Yankee Stadium.” The story originally ran in the fall of ’88 in the Village Voice, and appears here with the author’s permission and his postscript, in which he reveals his subsequent clashes with his editors both at the poker table and over what exactly constitutes “journalism.”

“The Regulars”

By Ivan Solotaroff

There’s an evil-looking man with a pencil mustache in the last row of Yankee Stadium’s right field bleachers, leaning back against a 50-foot-high CITIBANK IS YOUR BANK sign. Immaculate in his tan fedora, sky-blue leisure suit, glowing white T-shirt, and white patent-leather loafers, he snorts the end of a joint through a gold roach-clip as the Toronto Blue Jays take the field for the bottom of the second inning, then begins to twist his arms and hands and fingers in suave convulsions, his mouth stretching into unnatural shapes as he trains his magnetizing gaze on Jays right fielder Jesse Barfield, pacing the well-lit grass of right field 90 feet below. I’ve been watching this man for months now, casting his limp-wristed spell on every American League right fielder not born in the Dominican Republic, and I have learned to fear his power. Midway through this late-August Yankee homestand, I feel a tingle in the back of my skull every time he starts conjuring.

Teena, a paper-thin Hispanic woman known among the Regulars as the Secretary of Da Fence, sees the effect he’s having on me, and yells up at him to Cut That Voodoo Bullshit Out. “He isn’t no Yankee fan,” she assures me, tucking a loose blond curl back into her impromptu Mohawk. “Bullshit Voodoo Man. I show you what’s a Yankee fan.”

Teena gathers the wealth of gold chains on her neck, and her yellow ashtray eyes cross as she looks down to exhibit the ornaments to me: six variations of the Yankee logo in 14 or 16 karats; a small, diamond-studded baseball and bat, accompanying the word YANKEES; and the brightest is a solid-gold 31, for Yankee all-star right fielder Dave Winfield.

“I show you the biggest Yankee fan there is,” she says, taking my hand and leading me down to Row A to meet Chico, a happy 300-pounder in a cobalt-blue Yankee jacket with a homemade 31 sewn on the back. “You Ain’t Nothin’ But a Hound Dog” is blasting on the P.A., and Chico’s rocking out an imaginary bass guitar, all 10 fingers moving in spidery patterns. “He’s been in the papers lots,” says Teena. “Hasn’t you, Chico?”

“Bellevue,” Chico agrees, keeping good time on the bass. “New York’s hometown paper. Intensive care. Times Square. Fifteen years.” At Teena’s prodding, he reaches in the pocket of his Yankee jacket for a half-dozen Polaroids of himself and an equally large woman having sex in a living room furnished entirely in red velvet.

“Motherfucking co’sucker, Jesse Barfield, maricón,” Chico screams suddenly. He takes his Polaroids back and pivots on his heel with surprising agility to rock the entire stadium, yelling, “Jesse Jesse fuck you messy” until the inning begins.

In 1973, Rick Goldfarb was my classmate at the Bronx High School of Science, a studious, awkward kid no one knew much about, except that he had a good head for numbers and a job selling beer at the Stadium. Over the years he’s kept a CPA practice going on Allerton Avenue in the South Bronx, from January to April 15; from April 16 through October, he sells beer in the third base box seats for the first four innings, and from the fifth on, he’s “Cousin Brewski,” the sweetest and loudest guy out here.

“How are you? How are you? How are you?” he greets me from 10 rows away. “I’ll tell you everything you wanna know about the Regulars. They’re the best fans out here. Class. They know everything you wanna know. Teena’s got it all: the batting averages, all the ERA’s, all the Won and the Lost. Bob the Captain knows every word of the ‘Gang Bang Song,’ the ‘Get the Puck Out Song,’ ‘Syphilis,’ the ‘Alibi Song,’ all the fabulous songs. And over there’s Melle Mel. A big rap star [of Grandmaster Flash], one of the originals.“

Rick’s mouth widens into a horse grin as Melle begins leading the Regulars in a rendition of “Camptown Races,” lyrics modified to honor Chili Davis’s alleged anal-passive tendencies. “Famous? Melle?” Rick asks himself rhetorically. “Oh-h, is he famous! Sees everything going on out here, too. The others tend to drift a little. Frank’s out here every day, brings candy”—

Rick excuses himself to go to the first row to join the second verse

Jesse takes it up the ass

Doo-da, doo-da

Jesse takes it up the ass

Oh, da-doo, da-day

then climbs back up the concrete steps, saying, “Where was I? Where was I? Where was I? Frank brings candy for the kids, Turkish Taffy sometimes. He’s got a heart of gold out here, do anything for anyone. If he knows you. We got business students from Clark University, summer interns from The Nation. There’s Buttonhead, sells all the different buttons—RED SOX SUCK, TIGERS SUCK, A’S SUCK, METS SUCK, STEINBRENNER SUCKS. And there’s Yankee Joints, sells what he sells. They’re here when it’s 100 degrees, when it’s 40. They brought in a huge plate of Spanish rice last week, chicken with chick peas, stuffed cabbages, all those greens with the good olive oil dripping off. Just one big heart of gold, getting old.”

I ask Rick how many years these people have been coming here, a question that brings out the accountant. “Figure, say, 100, 115 individuals total,” he calculates, surveying the 12 rows in front of us. “Then, maybe 20, say 17 years apiece, average. So you’re looking at what, maybe 1,900 years out here. But those are just numbers,” he says, waving an index finger. “You gotta figure in the human factor.”

The Yankees, 2-8 in their last 10 games, come into the fifth inning down by a familiar four-run count. Frank and his friend Ike are already ingesting their time-honored slump-remedy: Many Jumbo Beers. It only takes Don Mattingly’s lead-off single to left to make them crazed. After the obligatory four notes of the Hallelujah Chorus sound from the Stadium organ (echoed by Frank and Ike’s “O! the Mets suck!”), they get the first 12 rows up and pointing at Jesse Barfield:

U, G, L, Y

You ain’t go no alibi

You uglay

You uglay

P, A, P, A

We all know your papa’s gay

He’s homo

He’s homo

M, A, M, A,

We know how he got that way

Your mama

She uglay

The entire bleachers looking on, Melle Mel decides to create some game-changing noise. Flipping his night-game shades up, tightening the doo rag on his head, he spies a newcomer in a Hawaiian shirt. “BOOK HIM,” he commands, and the Regulars obey bynah-nah-nah-ing the “Hawaii Five-O” melody in the man’s face until, with a longing look at the blue seats of the loge level, he’s up on his bench and surfing it.

“If the Yankees are the best team in the world,” Melle yells above the roar of a 4 train passing 10 feet behind the bleachers, “say Yo-o.” Hundreds agreeing—and #31 himself stepping up to the plate, 375 feet away—Melle has a moment worthy of the Great Cause. “Let me hear it, one time, for my man, Mr. Da-a-a-a-ve Winfield.” “Dave, Dave, Dave,” a huge crowd chants as Winfield looks at a strike. They’re still chanting “Dave” as Winfield whiffs on a second pitch, looks at a third strike, then lopes indifferently back to the dugout.

“That’s the greatest number of all about this sport,” Rick explains when I mention that Winfield’s strikeout doesn’t seem to bother anyone. “You fail two out of every three times, 66 percent of your professional life, and out here you’re God’s gift.”

Statisticians of the great American game would do well to analyze Ali Ramirez, a tall, white-haired man who brings a cowbell to the games in a bowling-ball bag. A serious student of the game, Ali won’t ring his bell until he feels a Yankee hit. For the last few weeks, I’ve been getting goose bumps every time Ali stands and unsheathes his bell; with the Yankees down now by four runs and two outs, no one on in the bottom of the sixth, I suddenly understand why: I’ve been hearing this bell in the distance my entire life, behind Phil Rizzuto’s hypnotizing psalmodies on WPIX, and I’ve learned to expect a Holy Cow (Rizzuto’s unfailing ejaculation for Yankee home runs), or at least a single, every time Ali rings the bell.

As Jack Clark steps up to the plate, Ali hammers out an eight-beat salsa rhythm, which is echoed by a drumming on the free seats by the Regulars that I can feel, 10 rows up, through my tailbone. He follows with a 16-count, then ends with a steady beat that gets a deafening ” Ay-oh” chant. It’s broken by an unmistakable crack of Clark’s bat, and a flurry of kids heading to the empty right-field grandstands, where Clark’s 370-foot homer soon lands 20 rows deep.

“The Gods have spoken,” yells Melle Mel, up on his seat and salaaming. “Prai-ai-se A-A-Ali!” Almost everyone in the bleachers obeys, a moving sight—350 people bowing in a wave to this quiet man wearing a barber’s shirt, cradling his bell and drumstick, already evaluating Don Slaught’s stance at the plate.

Apparently it’s rally time, for Ali rings out another eight-count. Before he can start his 16’s, another long-ball crack gets the entire bleachers on its feet. I look up in the klieg-lit sky over right field and see a baseball coming at me, then under my seat for my first baseman’s glove to catch it, then back up in time to see the ball falling in the trough penning the bleachers apart from the rest of the stadium—50 feet from Clark’s homer, and 15 feet to the left of the man with the bell.

Ali, ignoring the pleas of the Regulars, zips up his bowling ball bag as Gary Ward strikes out to end the inning. The timeless nature of baseball wafts over me like car exhaust as it dawns on me that I haven’t had a first-basemen’s glove for 20 years. Twenty rows up, the Voodoo Man is striking an Edith Piaf pose against the Citibank sign after his exertions.

By the seventh inning, timelessness has given way to insoluble tedium, and I organize a small press conference in the top rows with some of the Regulars: Bob Greco, machinist from Bergen County, and Captain of the Bleachers; Frank Herrera, a college baseball umpire with a major stutter, who talks endlessly about whom he’s willing to beat up for the Yankees; and a strange man named Big Bird, who seems to have an obsession with Australia: Tonight, he’s telling me about the difficulties of sending videos of the 1978 World Series to Melbourne. “He was there six weeks, six years ago,” Bob explains. “Still fuckin’ talkin’ about it.”

The Yankees seem to have fallen into the lull. Though they ended the sixth down only two runs, the Angels have pounded relief pitchers John Candelaria and Steve Shields for four runs. For Bob, Frank, and Big Bird, however, watching a routine single drop in the hole between Ward and Winfield for extra bases, it’s clearly not an important failure. “If you came here every day, you’d just get used to it,” Bob says as Teena climbs the steps to tell me to tell the world that every Yankee reliever makes her puke. “And you would grow to like it out here. You would see how it’s like the family unit. You yell a bunch of shit, 50 people yell out with you. Get into a fight, you got a hundred backers. Plus, you can see everything from out here. Call balls and strikes. You can see inside the dugouts ….”

“Tell him about the time we gave you a birthday cake,” Frank interrupts. “You were all choked up and shit.”

“Time out,” Bob says. “I wanna tell him about training camp in Lauderdale. So, I’m down there with Kevin and George, couple the Regulars—.”

“Tell him about the cake, you fuckin’ dick,” says Frank.

“Time out, Frankie. We’re driving from the hotel to the ball park, half an hour, 45 minutes maybe, looking at all these maps. After four days, we realize we’re half a mile from the stadium.”

Bob sees Frank standing up with a look of terminal displeasure, and decides to tell me about the cake: “So I’m out here one night and they’re singing, ‘Happy Birthday.’ They got a cake, so I sing with ’em. But when they get to the ‘Happy Birthday, dear…’ part, they’re like, singing my name.'”

Bob pauses, to let the mystery sink in. “It’s my 32nd birthday. The cake’s got my name on it, too. It’s probably like the biggest thrill of my life.”

The Blue Jays take the field for the bottom of the seventh, and Frank and Bob ask me if I’ve heard their “Mickey Mouse” cover:

Hey, Jesse!

M, I, C

See you real soo-oo-n

K, E, Y. Why-y-y?

‘Cause we don’t give a fuck about you

“I love that one,” says Frankie. “And, first time I heard the ‘Gang Bang,’ I was on the floor.” He stands up, glares at the air an inch above his head and five feet in front, and screams, “The Yankees suck what?” then begins punching the air. Bob shakes his head and finishes telling me about Lauderdale.

“So we get some pictures, the three of us with Dave, meet some other New Yorkers in the hotel—they weren’t there for the training, they were on some other business. The biggest thrill was with Dave. What else is new?”

“Do you guys know him?”

“Yeah, we know him. Not personally, on a social level, but he sees us on the street, he knows, ‘Yeah, the Bleachers.’ We give him a plaque last year, congratulating him for his sixth consecutive year hitting 100 RBIs. He didn’t do it, he ended up with 97, but we give him the plaque anyway.”

“I met Dave once,” says Frankie.

“Time out, Frankie. So we’re down there, waiting by the gate for Dave to come out. There’s a couple guys there, had their kids or something, and we ask, ‘Dave come out yet?’ And they’re like, ‘Don’t waste your breath, Dave don’t stop for nobody.’ So he comes out, and the three of us are like, ‘Dave, Dave, Dave.’ Big smile. He’s like, ‘What the fuck are you guys doing down here?’ signing autographs. He remembers the plaque. Suddenly”—Bob pauses to savor the irony—”the guys with the kids are like, ‘Hey, we’re with these guys.’ That was like the biggest thrill of my life.”

Frankie looks hurt. “I thought it was the cake.”

“Nah, that was the biggest thrill of my life out here,” Bob corrects him, standing up and brushing off his pants as he heads down to Row A. “Talk to the man, Frankie. He’ll make you famous.”

Against the backdrop of the “Get the Puck Out Song” and the “Gang Bang Song” (a series of knock-knock jokes ranging from “Eisenhower”/”Eisenhower Who?”/”Eisenhower late for the Gang Bang” to “Gladiator”/”… before the Gang Bang”), I listen to half an hour of Frankie’s fantasy life. It’s a familiar fantasy to anyone growing up in New York: being outnumbered and having the numbers to escalate.

“I would never suggest,” he begins, “for anyone to come out to the bleachers and to hit one of the Regulars. I would not suggest that. And I would never suggest what happened here, one time, when Yankee Joints got his bag taken by some guy. He asked for it back, and five guys stood up in his face, at him. So I walked over there, and, like, 50 guys jumped up behind me, it was like a wave. I tried to explain to these guys, I got, like, 50 guys behind me, and every last one of them’s willing to hit you. They don’t need no reason.”

I ask if there are a lot of fights out here. “This dude says, ‘Whenever there’s a fight, I never see you anywhere. Why?’ Why-y? You ain’t looking in the right place,” Frank answers. He seems convinced that it was me who asked the question. “If you ever see a fight,” he says, poking my chest hard, “look under the pile. Under the pile. That’s where you’ll find me. Under the fucking pile. But, like, if, like, this guy”—Frankie points to a fan two rows back—”like, if this guy were to hit Bob or Ike or Cousin Brewski, it would be suicide. And if I stood up in … his face”—Frank points to the same fan—”and said, ‘You gonna hit me, you gonna fucking hit me?’ I swear, 20 people will come behind me.”

Frank looks at the guy suspiciously, then tells me how five enormous security guards came to the bleachers for him one day last summer. “Now, that is the most idiotic thing in the world I have ever heard. If you got 2,000 fans and 3,000 guards, then maybe, maybe you could talk. But if you got five guards, I don’t care what size they are, I’ll throw 20 midgets on you to kick your ass. But they don’t think that way over there in Security.”

I ask Frank how he came to be an umpire.

“I was playing football and I got hurt bad. I could still move around and holler, but I couldn’t ever play again. I was going home, and the bus driver asked me did I want to umpire little-league ball with him. And I enjoyed it, a lot. See, what happened was, my first game, I threw the manager out. And I said, ‘Damn, I’m 13 and I just threw this 40-year-old man out.’ So, I grew up and went to umpiring school in San Bernardino. I do college now, and the Dominican Leagues in the winter. With a little luck, I’ll make it to the majors.”

Frank looks down at the field, where the Yankees have just gone down three straight, then over at the Regulars, who are singing “Syphilis.” “One day,” he nods his head, “I’ll be umping at the Stadium, and I would have to make a close call against this team.”

Frank continues nodding his head. “See, I know that would happen,” he adds with conviction, “And the Regulars would nail me. I know that. Fuck them. I call them like I see them. And I will be a Yankee fan till the day I die. I know that.”

A 4 train rumbles overhead, and Frankie starts thinking about something, shaking his head and moving his lips with a repeated, unspoken sentence. “Everywhere I go,” he finally says it. “Everywhere I go till the day I die.”

He stands up and looks down at the first rows. “Like, I was on the subway,” he says, “wearing my cap. And this guy’s wearing a Mets cap: ‘You should get a better cap.’ Get a better cap?! What?” Frankie takes his black Yankee cap off his head and pounds it into shape. “When you win as many World Championships as the Yankees,” he tells me. “When you win as many pennants. When you win as many division championships, as many World Series as this franchise, in its history, then you come back and see me.” Frank screws his cap back on his head, shoots me a hate-look, then heads down the steps to join the Regulars. “And I’ll meet you on this train,” he yells up at me, “3,000 years from now.”

This piece was my way of hiding out for the summer of, I believe, 1988. Nothing good going on, a piece already published in the Village Voice sports section, so I got my second journalistic “assignment”: the months of July and August in the cauldron of the old Yankee Stadium’s right-field bleachers. I didn’t get to file receipts for most of the games, as they would’ve come to more than the commission. The Voice paid 10 cents a word until you got a contract, so I probably got $400 or so for the piece.

It didn’t matter. It was very well received at the Voice—a rare chance for that excruciatingly politically correct rag to publish sexism, racism, and homophobia to comic effect. Crucially, it got me into their monthly poker game as well, and they were terrible players. That amortized those unclaimed receipts several times over.

It wasn’t all good, however. The managing editor kept kvelling one game—it was getting embarrassing. When he said, “I’d love to read your fiction sometime,” I didn’t think twice, and said, “You just did.” The story’s set over one game—at 4,000 words or so, there wasn’t space for more, and I had two whole months to squeeze in. My reputation as a “piper” continues to this day, which is fine by me. I believe that all journalism is fiction. If it’s any good. And fuck them anyway.

But I did get read the riot act from my best friend at the time, who’s gay, as well as another act read (luckily before sending the story in), from another best friend, who objected to an original draft which incorporated Frankie’s stuttering. It read very funny, but it was cruel; I understood that fully only when I later learned that Frankie had passed away.

I tried to find a copy of the original story online just now, of course hopeless: Like Elvis Costello sang, “Yesterday’s news is tomorrow’s fish-and-chip paper.” But it did lead me to Phil Bondy’s Bleacher Creatures, written after his summer spent with the Regulars, 15 years later. I was amused, would be the kind word, that he didn’t so much as reference the earlier article, as his title was lifted from the title my story ran under: That was a creation of the Voice‘s sports editor, and I didn’t much care for the inhumanity of the subjects it conveyed. If anything, I objected, they were human, all too human. When that didn’t fly, I did manage to get a bitch-slap of a title past a different Voice sports editor a decade later: on Mark Gastineau’s pugilistic career, which I entitled “Superhuman, All Too Superhuman.”

[Photo Credit: Don Rice via Lover of Beauty]

My in-laws got my wife and I some “Bomber Bucks” for Christmas, including with the gift their babysitting services so that Becky and I could get out to at least one game this year. It was a very thoughtful gift. Unfortunately, it turns out that Bomber Bucks can only be cashed in for tickets (not concessions or merchandise) and only at the ticket windows at Yankee Stadium. Adding insult to the difficulty of finding babysitting (thanks, Mom!), spending $25 on trains, and taking a three-hour round trip from suburban New Jersey to the Bronx simply to purchase tickets, the Yankee Stadium ticket windows didn’t open for business until five days after tickets went on sale to the general public via phone and internet.

When I finally got there on Friday, piggybacking the journey on a trip to mid-town for a “Bronx Banter Breakdown” taping (three segments coming Monday through Wednesday), I was informed that there were no bleacher seats left. Period. That the only seats to Red Sox games remaining were north of $300 a piece, and that of the six Sunday games my wife and I could both make, none had two available seats together in the grandstand. After playing what amounted to a game of battleship with the amicable young woman on the other side of the glass (“May 16” “miss” “August 18” “miss” “July 25” “miss” . . .), I was finally able to use up the gift certificate on two pairs of nosebleed seats to weeknight games and a single ticket in the grandstand for a Monday night game in May against the Orioles. Remember, tickets had only been on sale to the general public for a week. Frustrated and disappointed, I stuck my tickets in my bag, wheeled around and was greeted by this:

It is a monument to corruption, greed, and the failures of our municipal and state governments to act in the best interests of the people they are supposed to represent, and a vile and disgusting insult to all but the wealthiest of Yankee fans.

. . . what they’ve really done is take affordable seats away from the common fan who can only afford to sit in the upper deck or bleachers of the current Stadium and relocated them to parts of the ballpark only the wealthy can afford. To make matters worse, the new Stadium will hold 4,561 fewer fans, and you can surely guess which seats are being slashed. With a smaller bleacher capacity, a smaller upper deck, and an increase in luxury and outdoor suite seating, the new Stadium will be spitting out fans of modest means to accommodate the organization’s target audience of free-spending fat cats.

That was what I wrote about the new Yankee Stadium back in September 2008, three days before the final game in the real Yankee Stadium, a game Becky and I would watch from the right-field bleacher seats that were ours every Sunday, Opening Day, and Old-Timers’ Day for the old park’s final six years. Yesterday, I felt the harsh reality of those words.

To be honest, my fanaticism has receded in recent years, in part due to professional necessity and in part due to the team’s stadium shenanigans, which have soured me significantly, but I still consider myself a Yankee fan. I inherited it from my grandfathers. I paid my dues as a kid growing up in the ’80s when the Mets were hip and Yankee hats were about as cool as bell bottoms and mutton chops. I indoctrinated my wife in the ’90s, and I’m not about to abandon her or that familial tradition now. I hope to introduce my daughter to the joys of baseball through her inherited Yankee fandom. I just wish the team my family and I root for wanted or even needed us just a little.

I really enjoyed the fact that the Yankees brought out the U.S. Army Field Band to kick off Sunday’s pre-game ceremonies by playing a pair of Sousa marches thereby echoing the band John Philip Sousa himself led on Opening Day in 1923.

This ain’t that:

I spent nearly 12 hours at Yankee Stadium yesterday. What follows, believe it or not, is the short version of that experience.

At roughly half past midnight last night, my wife, Becky, and I were standing next to our car in the darkened parking lot near the Harlem River, finishing off the soft-serve ice cream cones we had picked up on our way under the Major Deegan. As Yankee Stadium sat glowing behind us, the blue aura of the stadium lights reaching up toward the half moon set low in the sky over center field, Becky compared the emotions we were feeling to a junior high graduation. We will still see the same people and do the same things next year, she reasoned, it will just be in a different place. I resisted the comparison at first, rattling on about history and landmarks and what will be lost when the Stadium is razed, but upon reflection, and still flush with the emotion of the night as I write this in the wee-morning hours, I’ve found the truth in her comparison.

Becky and I were high school sweethearts, and though our school days have receded deep into our past, they remain with us both through our relationship with each other, through our closest friends, most of whom we can also trace back to high school, and through the many other ways in which those years shaped our lives and set us upon the course we are on today. Becky was sad to leave high school, for reasons I didn’t completely understand. I couldn’t wait to leave it behind. Perhaps that’s why it took me a moment to find the truth in her statement.

As I wrote earlier this week, the strongest of my many mixed emotions leading up to last night’s final game at Yankee Stadium was anger. That anger has expressed it self in criticism of the public expense, abuses, and design flaws of the new Stadium, but ultimately my anger stems from the private hurt of being evicted from a place that I consider home. I imagine that’s how Becky must have felt upon graduation, angry that forces beyond her control were robbing her of a place of comfort and familiarity, a place filled with elemental memories, and place in which she had grown from a timid 14-year-old girl into a confident young woman.

My feelings about Yankee Stadium are similar. Just 12 years old when I attended my first game there, I was a kid caught between childhood and maturity, still searching for my place after the dissolution of my parents’ marriage and amid their subsequent relationships, still searching for an identity of my own, but beginning to sense that baseball might play a part. Last night I left that Stadium for the last time a grown man of 32, a husband hoping to become a father, a man who has found true happiness in his own marriage and who has followed his muse through a variety of rewarding and creative endeavors, not the least of which is the blog you’re reading right now.

Other than my parents, the only constant in my life throughout that journey has been baseball, specifically Yankee baseball, and though I’ve been in locker rooms and press boxes in other ballparks, my relationship with baseball has been no more intimate than when I’ve been in the stands in Yankee Stadium. Now that’s gone, and I’m hurt, and angry, and sad, but I’m also hopeful and excited about what the next twenty years might bring, for both myself and the team, and about the people I’ll be able to share those experiences with. Perhaps most of all, I’m thankful. Thankful that I had the opportunity to see scores of games at the old ballpark. Thankful that I could share those experiences with Becky, both of my parents, and a variety of friends from across twenty years. Thankful that I have this forum to express myself and to share my thoughts and feelings with countless readers, who in turn share theirs with me and each other. Better yet, I’m thankful that I have lived a life privileged and pleasant enough that the closing of a sporting venue could have such a profound impact on me. While I’ll never get to set foot in Yankee Stadium again, this morning I’m going to be thankful for the many wonderful things I do have rather than be bitter about the one thing I just lost.

I’ve never been to Yankee Stadium. Oh sure, I’ve seen the Yankees play in the Bronx more than one hundred times over the past 20 years, but Yankee Stadium, the limestone behemoth that was home to Yankee greats from Babe Ruth to Mickey Mantle is something I’ve only seen in books, grainy film footage, and in the background of old baseball cards. That cavernous coliseum, with its copper frieze trimming the roof that hung over the upper deck and its career-altering death valley in left center, was destroyed following the 1973 season. Its last game was a forgettable 8-5 Yankee loss to the Tigers that concluded an equally forgettable 80-82 fourth-place season for the home team.

Two and a half years later, in its place, sat a different Yankee Stadium. A modernized, yet instantly-dated, grey, concrete bowl filled with royal blue seats and orange light bulbs that relayed information from a flat-black scoreboard. The copper frieze had been melted down and replaced with a concrete replica that sat on a lower perch atop the outfield scoreboard, like an artifact on one’s mantle. The roof had been largely removed. The wall in left center was now 27 feet closer to home plate and would come in another 31 feet before I ever got to see it in person. Behind that wall, the three marble-and-bronze monuments that had formed a half circle around the flag pole in the grass of center field sat in concrete and were surrounded by a black chain-link fence that separated the two bullpens.

Still, though the structure had been changed, and the field which had played host to 27 World Series and two All-Star Games had been torn up and replaced, there remained a connection between the remodeled Yankee Stadium, as it would become unofficially known, and the original. Just as the Yankees inaugurated Yankee Stadium with the franchise’s first World Championship in 1923, the team inaugurated the remodeled Stadium in 1976 with their first World Series appearance in 12 years and followed that up with championships in 1977 and 1978. In its 33 years of existence, the remodeled Stadium hosted 10 World Series and two All-Star Games. Unless the Dodgers reach the World Series this year, no other stadium will have hosted more than four Fall Classics over that same span. The remodeled Stadium quickly established itself as a worthy successor to the original not because of its own grandeur, which was lacking, but because of the grandeur of the games which took place there.

When the last out at Yankee Stadium is recorded tonight, baseball won’t be losing a great piece of architecture; the remodeled Stadium is no beauty. What it will lose is the living memory of some of the game’s greatest moments. What makes Yankee Stadium great is not the concrete replica of the frieze in center field or the relocated monuments beyond the wall in left field. It’s not even the great views from the upper deck or the camaraderie and passion of the bleacher creatures. It’s the history that was made there.

One can look around the current park and see where legendary home runs by Aaron Boone and Scott Brosius fell into the left field box seats, Reggie’s moon-shot off Charlie Hough clanged off the black batter’s eye, homers by Tino Martinez, Derek Jeter, and Chris Chambliss made post-season history by clearing the wall in right, with and without help. One can envision Mariano Rivera and Goose Gossage appearing through the bullpen gate in left center, Derek Jeter diving into the stands behind third base, David Wells punching the air and David Cone falling to his knees after the final outs of their perfect games. One can see Dave Righetti, Jim Abbott, and Dwight Gooden celebrating no-hitters, Thurman Munson crouching behind home plate as Ron Guidry strikes out 18 Angels, Don Mattingly bringing down the house with a home run into the right-field bleachers, Dave Winfield ripping bullets down the left field line, Rickey Henderson and Mickey Rivers burning up the bases, Willie Randolph turning two, Tom Seaver, Phil Neikro, and Roger Clemens winning 300, Alex Rodriguez hitting 500, and George Brett storming out of the visitor’s dugout, a victim of Billy Martin’s chicanery. One can also see Paul O’Neill meekly slumping his shoudlers as an entire Stadium chants his name, Reggie doffing his batting helmet to the crowd in front of the home dugout, Charley Hayes squeezing the final out of the 1996 World Series, Wade Boggs riding a police horse around the warning track, and both Jackson and Chambliss plowing their way through the swarms of celebrating fans toward the safety of the clubhouse.

Though the field has been torn up, replaced, moved, and lowered, it doesn’t take much imagination to envision the old park. In fact, that has been one of my favorite things to do when visiting the Stadium. I’d squint at the left-handed batters box and imagine Babe Ruth taking a mighty swing and christening the new park with a home run or Lou Gehrig, hat in hand, addressing the crowd. Looking around, I could see Joe DiMaggio kicking the dirt near second base, Mickey Mantle launching a ball off the frieze, Jackie Robinson breaking for home, Yogi Berra leaping into Don Larson’s arms, the Dodgers celebrating Brooklyn’s first and only championship, Roger Maris circling the bases after number 61, and Bobby Murcer chasing a ball around the monuments in center. Because the Yankees were in the World Series with such regularity, all but a select few of the game’s greats (most of them Cubs) played there, from Ty Cobb, to Ted Williams, to Tony Gwynn, Walter Johnson, to Sandy Koufax, to Pedro Martinez, Jackie Robinson, to Curt Flood, and Roberto Clemente, and so on. In 1928, Knute Rockne implored his team to “win one for the Gipper” there. In 1938, Joe Luis beat Max Schmeling there. In 1958, Johnny Unitas beat the New York Football Giants in the NFL Championship Game there.

That is what will be lost. Not the building, but the place and the tangible connection to what happened there. The Yankees may only be moving a few hundred feet to the north to play on a field of similar dimensions in a ballpark with an identical name, but Yankee Stadium, the real Yankee Stadium, in both its incarnations, will soon be resigned to the page, the screen, and the memory of those who were fortunate enough to have seen a ballgame there, whether they witnessed a great moment, or simply gazed out at the field and imagined all the great moments that had come before.

It was a near perfect afternoon in the Bronx yesterday as the Yankees and Orioles played the final day game at Yankee Stadium. Amid sharp shadows and under a cloudless sky, the Stadium gleamed, the cool early autumn air adding a crispness to the day. The Yankees and Orioles played scoreless baseball for eight-plus innings, but the lack of action on the field mattered little as most everyone on hand and watching at home was more concerned about drinking in the doomed ballpark, which has rarely looked more welcoming or more vibrant.

Afredo Aceves got things started off in style in the first inning. Following a Brian Roberts lead-off double, Adam Jones popped up a bunt in front of the mound. Aceves, who has shown himself to be a solid infielder, caught the ball on a lunge before tumbling forward to his knees. He then spun to double Roberts off of second, but Roberts had been running on the pitch and had actually rounded third base slightly, so rather than throw to Cody Ransom covering second base, Aceves, with a big grin on his face, jogged the ball over to second for an unassisted double play, a play rarely turned by a pitcher (paging Bob Timmermann).

Aceves wouldn’t allow a runner past second base all day, and after six innings and 92 pitches, he was replaced by Brian Bruney, Damaso Marte, and Mariano Rivera, who kept that streak intact. The Yankees didn’t do much better against lefty spot-starter Brian Burres. With two outs in the first, Bobby Abreu doubled and moved to third on a wild pitch, but Alex Rodriguez popped out to strand him, and the Yankees didn’t get another man past second until the bottom of the ninth.

Though it would ultimately prove a fitting conclusion to a beautiful day, the bottom of the ninth started off ominously when a 1-1 pitch got away from rookie reliever Jim Miller and hit Derek Jeter on the back of his left hand. Jeter spun to avoid the pitch, but it caught him flush and sent him skipping toward the visiting batting circle in obvious pain. Joe Girardi and trainer Gene Monahan quickly attended to Jeter, who was the DH yesterday to give him a breather before today’s final game at the Stadium, and almost immediately pulled Jeter from the game. Jeter didn’t make a fist with the hand when Monahan was checking him out on the field, and as he headed into the tunnel toward the clubhouse, Jeter slammed his batting helmet on the dugout floor. Fortunately, post-game x-rays were negative and Jeter is expected to be in the lineup for the Stadium’s finale . . . of course.

Brett Gardner ran for Jeter at first base and stole second base easily on Miller’s first pitch to Abreu. After Miller fell behind Abreu 3-0, Orioles manager Dave Trembley decided to make use of that empty base and pass the buck to Alex Rodriguez. Rodriguez took two strikes then hit into a near double play, but managed to beat out the relay to put runners on the corners with one out for Jason Giambi. Trembley called on veteran lefty reliever Jamie Walker to pitch to Giambi, and Walker responded by striking Giambi out on six pitches. Rodriguez stole second on strike three, so Trembley had Walker put Xavier Nady on base and pitch to fellow lefty Robinson Cano. Cano, who still holds the distinction of having hit the last home run at Yankee Stadium, jumped on Walker’s first pitch, delivering a line-drive single just to the right of second base, plating Gardner with the winning run.

So in the final day game at Yankee Stadium, the Yankees beat the Orioles 1-0 on a walk-off single by Robison Cano. Mariano Rivera got the win, and the Yankees staved off elimination for at least one more day. The day was so close to perfect that, in some peverse way, I almost wish yesterday’s game was the last ever at the Stadium. The only way tonight’s game could be better would be for a Yankee to hit a home run and for Jeter to be somewhere other than the trainers’ room when the game ends.

The just-completed series against the White Sox had some interest beyond the impending closing of Yankee Stadium thanks to Chicago’s fight for the AL Central, Mike Mussina’s still-active quest for 20 wins, the return of Phil Hughes to the Yankee rotation, and the major league debuts of three Yankee prospects last night. This weekend’s series against the Orioles has none of that. These last three games will be about Yankee Stadium and nothing else. With that in mind, here are the three other opening and closing dates in the Stadium’s 86-year history:

April 18, 1923 – the first game at Yankee Stadium, Yankees beat the Red Sox 4-1 behind Bob Shawkey, who scored the first run at the new park on a single by third baseman Joe Dugan in the fourth inning. Ruth followed Dugan with a three-run homer, the Stadium’s first. Second baseman Aaron Ward had picked up the park’s first hit in the previous inning.

Sept. 30, 1973 – the final game at the original Stadium, Yankees lost to the Tigers 8-5 as Fritz Peterson and Lindy McDaniel combined to allow six runs in the eighth inning. Backup catcher Duke Sims, in his only start of the year, hits the last home run at the old park in the seventh. Winning pitcher John Hiller gets first baseman Mike Hegan to fly out to center fielder Mickey Stanley to end the game.

April 15, 1976 – the first game at the renovated Stadium, Yankees beat the Twins 11-4 with Dick Tidrow picking up the win with five shoutout innings in relief of Rudy May and Sparky Lyle getting the save. May gave up the first hit and home run in the remodeled Stadium to Disco Dan Ford in the top of the first. Twins second baseman Jerry Terrell, who led of the game with a walk, scored the first run ahead of Ford. The first Yankee hit was delivered by Mickey Rivers in the bottom of the first. The first Yankee home run at the redone park would come off the bat of Thurman Munson two days later.

The relocated St. Louis Browns first played at the Stadium as the Baltimore Orioles on May 5 and 6 of 1954, losing to Eddie Lopat and Allie Reynolds by scores of 4-2 and 9-0. The O’s first visit to the renovated stadium came in a three-game weekend series starting on May 14, 1976. The O’s took two of three in that series, beating Catfish Hunter in the opener. The first batter in that game was Ken Singleton, who struck out looking, but the next six Orioles delivered hits off Hunter, among them a two-run homer by O’s center fielder Reggie Jackson (!) as the O’s cruised to a 6-2 win behind Ross Grimsley.

The relocated St. Louis Browns first played at the Stadium as the Baltimore Orioles on May 5 and 6 of 1954, losing to Eddie Lopat and Allie Reynolds by scores of 4-2 and 9-0. The O’s first visit to the renovated stadium came in a three-game weekend series starting on May 14, 1976. The O’s took two of three in that series, beating Catfish Hunter in the opener. The first batter in that game was Ken Singleton, who struck out looking, but the next six Orioles delivered hits off Hunter, among them a two-run homer by O’s center fielder Reggie Jackson (!) as the O’s cruised to a 6-2 win behind Ross Grimsley.

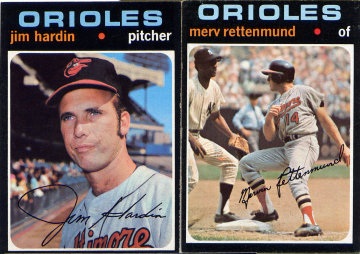

For the curious, the action depicted in the Merv Rettenmund card pictured here occurred on August 9, 1970 in the seventh inning of the first game of a Sunday doubleheader. With the O’s leading 1-0 behind Jim Palmer, Rettenmund led off the seventh with a double off Fritz Peterson. Andy Etchebarren then hit a hot shot to third base that Jerry Kenney either booted or bobbled, allowing Etchebarren to reach and Rettenmund to advance. The photo on the card freezes the action as Kenney, ball in hand, checks Rettenmund at third base. The O’s would go on to score three unearned runs in that inning, but the Yanks got two in the eighth and two in the ninth to tie it, the latter two on a single by Roy White after Earl Weaver had replaced Palmer with Pete Richert. White would later end the game in the 11th with one out and Horace Clarke on first base by homering off Dick Hall to give the Yankees a 6-4 win.

Finally, here’s an account of the last game at the original Stadium from Glenn Stout’s outstanding Yankees Century:

The Yankees ended the season on September 30, closing down old Yankee Stadium to accommodate the scheduled renovation. In the final week of the season, the Hall of Fame hauled away a ticket booth, a turnstile, and other memorabilia. Anticipating souvenir takers, the club had already removed the center-field monuments and a hoard of equipment scheduled to follow the Yankees to Queens.

The club hired extra security to head off bad behavior, but the crowd of 32,328 arrived at the Stadium in an ugly mood and packing wrecking tools. Disappointed at the late season collapse, banners urging the Yankees to fire [manager Ralph] Houk ringed the park.

The game was only a few innings old when it became clear that souvenir hunters weren’t going to wait. In the outfield and the bleachers fans turned their backs on the game and started demolishing the park. The Yankees took the lead over Detroit but lost it in the fifth [sic]. When Houk came to the mound to change pitchers, exuberant fans waived parts of seats over their heads like the angry they had become.

As soon as Mike Hegan flied out to end the 8-5 loss, 20,000 fans swamped security forces and stormed the field. The Yanks had plans for objects like the bases, but the mob had other ideas. First-base coach Elston Howard scooped up the bag for a scheduled presentation to Mrs. Lou Gehrig, but he had to fight his way off the field, clutching the base like a fullback plowing through the line. Cops stood guard at home plate to make sure it went to Claire Ruth, but a fan stole second base, and third was nabbed by Detroit third baseman Ike Brown. Some 10,000 seats ended up being pulled loose.

Last night, Andy Pettitte had one bad inning, the bullpen couldn’t hold the line, the offense couldn’t break through, and the Yankees lost 6-2. Sing me a new song.

As early as tomorrow this game will be remembered for just one reason. In the bottom of the first inning, Derek Jeter hit a hard grounder to third base on the first pitch he saw from White Sox starter Gavin Floyd. Sox third baseman Juan Uribe was playing in and dropped to one knee in an attempt to backhand the ball. Instead it shot through his legs. Jeter was awarded a hit, which pushed him past Lou Gehrig as the man with the most hits in the history of Yankee Stadium. It looked like an error to me, but Jeter made that irrelevant with a single in the fifth.

I mocked the attention lavished on Jeter for passing Babe Ruth for second on the Yankees’ all-time hit list, and YES’s coverage of last night’s hit and the hits leading up to it–particularly Michael Kay’s call of the hit (“Hit or error? Error or history?”)–was every bit as over-the-top if not moreso, but I actually think this record is pretty nifty. For one thing, it’s an actual record. For another, as Kay histrionically pointed out on the broadcast, it’s a record that can’t be broken. Sure, Gehrig had far fewer at-bats at the old Yankee Stadium than Jeter has had in the remodeled one, but there’s a purity and an absoluteness to “the most ever” that even applies to Barry Bonds.

Best of all, this is a record that honors not just the man who broke it, but the Stadium in which it was achieved. Yankee Stadium will go dark for good six days from now, but though there will never again be a meaningful game played in the old yard, and the Yankees as an organization have completely punted the opportunity to do something special for the final season of baseball’s most significant ballpark, Jeter was able to give us one last piece of history, and a private kind of history at that. For all of the great performances, accomplishments, and players who have graced the field on the southwest corner of 161st and River Ave over the past 86 years, the player who got more hits on that piece of real estate than anyone else ever has or ever will is Derek Jeter. I think that’s pretty cool.

Yesterday’s game was the last the Red Sox will ever play at the first Yankee Stadium. It was also the last I’ll ever see from the seating bowl of the old ballpark. I have two games remaining in the bleachers this season, including the Stadium’s final game against the Orioles on September 21, but that final game will be overrun with hype, anxiety, and mixed emotions. In providing two other, more specific “last”s, yesterday’s game provided me with a sense of personal closure regarding the old park.

Twenty years ago almost exactly, I saw my first game at Yankee Stadium from a seat in the front row of the upper deck in right field. The Yankees won that night on a walk-off home run in the bottom of the ninth by Claudell Washington. Yesterday afternoon, I was a few rows higher behind home plate and the Yankees won on a walk-off single in the bottom of the ninth by Jason Giambi. I’ll save my reminiscences of the games in between for another time, but I wanted to share a few of the photographs I took of yesterday’s game.