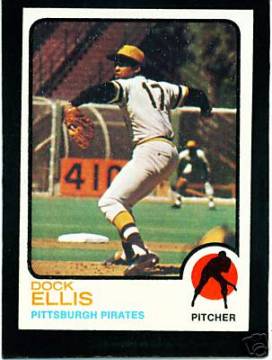

This 1973 Topps card of Dock Ellis (No. 575) shows the talented but temperamental right-hander where he seemed to feel most at home—on the pitching mound. The photograph, taken at a game at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park, is very similar to his 1972 "In Action" card, which appears to have been snapped in the same game but only a moment sooner in his pitching motion.

The word "snapped" might have applied to Ellis at various times during a successful and storied major league career. At times, the behavior of the Pirates’ right-hander would have qualified him for work in an episode of "The Twilight Zone." In 1970, Ellis pitched a no-hit game against the expansion Padres. (The Padres had only two good hitters in their lineup back then—Nate Colbert and Downtown Ollie Brown—but a no-hitter’s a no-hitter.) In and of itself, there’s nothing bizarre about such an accomplishment, which can represent the pinnacle of a pitcher’s performance. Years later, however, Ellis revealed that he had forged the masterpiece only hours after ingesting considerable amounts of LSD.

And then came the ugliness of a 1974 game, in which Ellis displayed his determination to punish the Reds for some condescending pre-game words they had said about the Pirates. (The Reds had a recent history of beating the Bucs; Ellis felt his teammates needed a wakeup call.) In the first inning, Ellis proceeded to hit each of the first three Reds’ batters—Pete Rose, Little Joe Morgan, and Dan Driessen—with pitched balls. With three of his first five pitches having hit his intended targets, Ellis continued his assault on Cincinnati’s lineup. He threw two pitches behind the head of Tony Perez before eventually walking the Hall of Fame slugger. With one run already having been forced in, Ellis refused to let up on his game plan. He threw two pitches at Johnny Bench that barely missed making contact. Amazingly, the home plate umpire allowed Ellis to remain in the game. (Obviously, this was not baseball in 2008.) But his manager, Danny Murtaugh, mercifully walked to the mound and removed Ellis before he could do any additional damage.

In perhaps his most celebrated incident (though not as controversial as his efforts to bean every member of the "Big Red Machine" or his pitching a no-hitter under the effects of illicit drugs), Ellis walked out onto the field before a 1973 game against the Cubs wearing a head full of hair curlers. The incident shocked several of his Pirates teammates, manager Bill Virdon, and Commissioner Bowie Kuhn. The latter’s opinion mattered the most; he threatened to fine and suspend Ellis if he continued to appear on the playing field looking like James Brown in a dressing room. Much to the delight of the commissioner, Ellis eventually backed off on his insistence on wearing curlers and restricted them to the clubhouse—or presumably to his home—for the balance of his career. Unfortunately, no one from Topps had been at Wrigley Field that memorable afternoon to snap a photograph of Ellis in his best "just-out-of-the-showers" look.

All of these bizarre stories involving Ellis have become pertinent again given the revelations of the past week. On Sunday, I was distressed to read a story in the New York Post about Ellis and his health, which has suddenly turned much worse over the past six months. A former Yankee—he pitched for the franchise in 1976—Ellis has lost 60 pounds since last fall, when he was diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver. Ellis needs a liver transplant soon; otherwise, the outlook is dire.

Ellis has certainly made more than his fair share of mistakes over the years, including his ill-advised usage of LSD prior to a game, his attempt to turn the Reds into human pin cushions, and his repeated efforts at undermining his managers. But almost all of that behavior occurred during Ellis’ playing days in the sixties and seventies, while he was trapped in a haze of alcohol and drug abuse. After his retirement in 1980, Ellis successfully abandoned his drug addiction and used his experiences to become a counselor against drugs and alcohol. An emotional public speaker, Ellis has worked diligently to advise youngsters not to repeat his own mistakes. Beginning early in his career, Dock has also made efforts to help prisoners in the Pennsylvania state penal system, soliciting their input in making suggestions for prison reform.

Considering his own personal reforms and the social consciousness that Ellis has displayed, he has become one of the game’s good guys. Let’s say a prayer that he receives some financial help for his mounting medical bills, which have become more problematic given his lack of health insurance. More importantly, let’s hope Dock receives that much needed liver transplant—quickly, before we lose a colorful character who began to find his way only 25 years ago.

Bruce Markusen’s upcoming book, Out of Left Field, includes a lengthy profile of Dock Ellis.