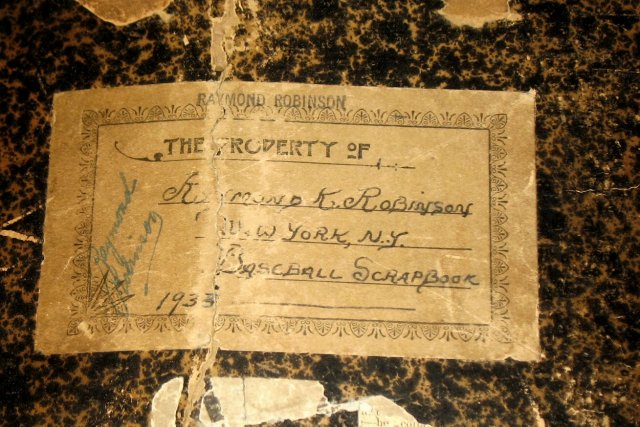

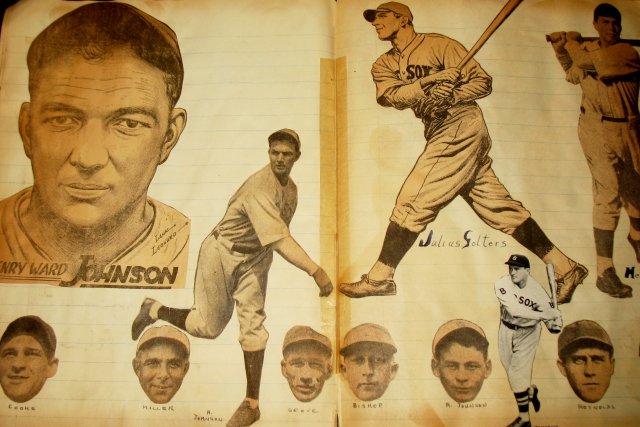

Not so long ago, a good friend of mine encouraged me to feel comfortable promoting myself. While it doesn’t come naturally for me, I figured, what the hell, I can talk about Pat Jordan’s writing all day long. The Best Sports Writing of Pat Jordan is coming out just before Opening Day. Each week until then, I’m going to pick one of Pat’s stories that can be found on-line and feature it in a post. Leading off is a fun piece he did a few years ago for the New York Times magazine on Daniel Negreanu, the all-star poker player (the story was featured in The Best American Sports Writing 2006, edited by Michael Lewis).

Card Stud (Originally published, May, 2005.)

Negreanu claims not to have much interest in money, except as a means of keeping score. After he won that $1.8 million at the Bellagio, he bought six videos and put the rest of the money in poker chips in a lockbox at the casino as if it were a bus-station locker. The chips are still there. The $1.1 million Negreanu won in Atlantic City was converted into $300,000 in cash and an $800,000 check. Back home in Las Vegas, he discovered that he left the check in his hotel room; the maid threw it out, and Negreanu had to fly back for another check. “I don’t believe much in banks,” he says. “Although I do have one bank account with not much in it, just a couple hundred thousand.” He also doesn’t believe in credit cards, or buying anything he can’t afford to pay cash for, which is why he always travels with a wad of $100 bills held together with an elastic band.

Negreanu has two basic rules for playing poker. First, maximize your best hand and minimize a mediocre hand. Too many novices play too many mediocre hands when not bluffing, which increases their chances of losing. Great players only play hands when they have “the nuts,” or unbeatable cards; otherwise they fold hand after hand. Second, play hours, not results. Negreanu sets a time limit for his play and sticks to it, whether he’s winning or losing. If he goes beyond his time limit, he risks playing “tired hands” when he is not sharp. (Before a tournament, Negreanu gives up alcohol and caffeine. “I do nothing, to numb my brain,” he says, “except watch poker film — just like an N.F.L. team before the Super Bowl.”)

Negreanu says that most great players are geniuses, then lists the kinds of genius they must have: 1) a thorough knowledge of poker; 2) a mathematical understanding of the probabilities of a card being dealt, given the cards visible; 3) a psychological understanding of an opponent; 4) an understanding of an opponent’s betting patterns — that is, how he bets with the nuts and how he bets when bluffing; and 5) the ability to read “tells,” or a player’s physical reactions to the cards he is dealt. Negreanu is a master at reading tells, although he claims it is an overrated gift, since only mediocre players have obvious tells. The best players, of course, have poker faces.

Negreanu says he can break down opponents’ hands into a range of 20 possibilities after two cards are dealt. After the next three cards are dealt, he says, he can narrow the possible hands to five, and after the last two cards are dealt, to two. “It’s not an exact science,” he admits, “but I can reduce the possibilities based on the cards showing, his betting pattern, tells, his personality and my pure instinct.”

Shulman, Card Player’s co-publisher, connects Negreanu’s success to his personality: “Daniel controls a table by getting everyone to talk and forget they’re playing for millions,” he told me. “He makes every game seem like a home game — you know, guys drinking beer and eating chips. They forget what’s happening. Plus, Daniel is the best at reading an opponent’s hands, as if their cards were transparent. He gets guys to play against him when he has a winning hand and gets them to fold when he has nothing. He’s the King of Bluffing. You know some guys can beat bad players and not good players, and some vice versa. Daniel does both.”

Beyond Negreanu’s knowledge and considerable intelligence, what makes him truly great is his aggressiveness in a game — his ruthlessness, some might say. He once bluffed his own girlfriend, also a professional poker player, out of a large pot at a tournament. “I bet with nothing,” he says, “and she folded. To rub it in, I showed her my hand. She was furious. She stormed into the bathroom, and we could hear her kicking the door, screaming, smashing stuff. When she came out she kicked me in the shin and said, ‘Take your own cab home.'” She is no longer his girlfriend.

(more…)