Our pal John Schulian‘s first novel, A Better Goodbye, was published late last week. Looking for something pulpy and nasty, look no further friends. This noir will keep you entertained and turning the pages. I recently chatted with John about writing his first novel. Dig:

Bronx Banter: Chico said, “Why a duck?” So I ask you: Why a novel?

John Schulian: Why not? A novel seemed like a logical progression for me. I’ve written for newspapers and magazines, I’ve written scripts in Hollywood, I’ve taught writing, I even wrote a couple of country songs after seeing four songwriters talk about their craft at Nashville’s Bluebird Café. Not surprisingly, nothing came of my songs, but I still loved the experience. It was just that a novel was much more my speed. When I had an idea for one and the time to write, it seemed like the most natural thing in the world.

You have to remember that I come from a generation where a novel was the Holy Grail for writers. Now, of course, non-fiction outsells fiction and screenplays have become the leading form for storytellers. But I was brought up on novels. My parents read me Robinson Crusoe and The Swiss Family Robinson. I discovered the Hardy Boys and John R. Tunis’s baseball novels on my own when I was in junior high. I played high school football with a bunch of upperclassmen who introduced me to the idea that a jock didn’t have to be ashamed if he liked books, especially books by J.D. Salinger. I confess that I bought Updike’s Rabbit, Run because I thought it was about a basketball. Okay, so I wasn’t the most sophisticated kid in the world. It didn’t stop me from losing myself in other novels, even those my English teachers assigned, like 1984 and To Kill a Mockingbird. The habit of a lifetime was formed in those years. I became a committed reader.

When I began writing professionally, when putting words on paper put food on my table, it was inevitable that I would think about writing a novel. I was always looking for a way to use fictional devices in my journalism. I went out to cover stories, whether they were championship prizefights or political corruption trials, in hopes of finding scenes that would capture the moment and perhaps speak to some larger truth. I wanted to hear what people were saying to each other, the dialogue that grows out of triumph or tragedy or whatever else they might be experiencing. I wanted to see how those scenes revealed the character of the people living them. I wanted the drama of real life.

It wasn’t until I was a newspaper sports columnist, primarily in Chicago, briefly in Philadelphia, that I enjoyed the freedom to take that approach as far as I could. And people noticed. Or maybe I should say other sports writers noticed. So did the good woman I was married to then. But I ignored their encouragement to write a novel. I liked being a sports columnist – the big events, the great old ballparks, the man-on-the-move datelines, the company of other writers, even the daily wrestling match with the language. The job consumed me, and on top of it, I was usually freelancing a magazine piece on the side. That didn’t leave a lot of time for tackling what I considered the greatest challenge for a writer – a novel.

Everywhere I looked in journalism back then, novelists were emerging. Dan Jenkins made the most noise with his bestselling Semi-Tough. Then someone recommended Bud Shrake, Jenkins’ running mate from Sports Illustrated, and I gobbled up two of his novels, Strange Peaces and Blessed McGill. It seemed inevitable that Jimmy Breslin and Pete Hamill, among newspaper columnists, would make waves in fiction. But first place in that category belonged to Pete Dexter, a stable mate of mine at the Philadelphia Daily News, who wrote a terrific first novel called God’s Pocket and then knocked the book world on its ass with Paris Trout. The surprise in all this was a copy editor at the Chicago Sun-Times – a quiet, unpretentious guy named Charles Dickinson who was writing wry, heartfelt novels about small-town America that got him compared to Sherwood Anderson and Sinclair Lewis. The big names at the paper were Mike Royko and Roger Ebert, and I did all right, too, but in one very important category, Charles Dickinson was ahead of us.

I suspected that John Ed Bradley was, too, the first time I ever read a story of his in the Washington Post. He was writing about his days as a tri-captain on Louisiana State’s football team, describing a night when he and his best friend, the team’s quarterback, were drinking beer as they sat on a hill overlooking the campus, talking about their dreams and what lay ahead of them. It wasn’t sports writing John Ed put before readers that morning; it was the work of someone who had novels in him.

He has written a bunch of them by now, along with an achingly beautiful memoir called It Never Rains in Tiger Stadium, and he has become a friend as well. It was in the latter capacity that he encouraged me to write a novel. That must have been thirty years ago, but I’ve never forgotten his encouragement, or that of others who said the same thing. I have to tell you, though, it’s one thing to get all puffed up because people think you possess that kind of talent and quite another to jump off the cliff, the way Butch and Sundance did. But on a January night more years ago than I care to remember, I finally sat down and wrote the first words of what became my novel, A Better Goodbye: “Too bad Barry wasn’t local. Suki would have told him her real name if he was.” I figured I didn’t have anything to lose. The fall would probably kill me.

BB: Okay, then. Why now?

JS: I needed something to keep me off the street. Besides, I convinced myself I was still writing well, and some ideas were taking shape in my head. I thought I better seize the moment. There didn’t seem to be anything left for me in TV. I’d done too much of it that was either bad or barely middlebrow. To make things worse, the rattlesnake who turned out to be my last Hollywood agent kept putting me up for science fiction shows I wouldn’t have watched with a gun at my head. Years later, when I saw Justified – part Western, part cop show, and an impeccable take on Elmore Leonard’s sensibility – I started drooling. But by then I was long gone from the TV wars.

I’m now 70, in case anyone is keeping score at home. It’s an age when you realize how precious time is. I may keel over dead before I finish this sentence, or I may live another thirty years. However much time I have left, I want to put it to good use and enjoy myself in the process. I loathe golf, which seems to seduce a lot of geezers. (Go ahead and kick your ball out of the rough, fellas. I’ll never tell.) The thought of traveling the world makes my blood run cold – I had my fill of airports, airplanes and hotel rooms when I was working on newspapers. I’d much rather be at my desk at home, trying to coax words out of my computer.

I have many friends who are wonderful writers yet hate the thought of writing, but I love it. I’ve been that way since I was a kid sketching out my own newspaper and movie ideas in the privacy of my bedroom. Now I suppose you can say I’ve come full circle. For the past ten or twelve years, I’ve only done things that appeal to me, writing essays and book reviews, putting together two collections of my sports writing, editing anthologies of other peoples’ work, writing and rewriting my novel and a handful of short stories, and trying like a madman to get my novel published in a world that is less kind to fiction with every passing day. Somehow I’ve succeeded in a modest way. I can call myself a novelist. And you know what? It tickles the hell out of me.

BB: Why a noir novel?

JS: Noir felt accessible, comfortable even though comfort obviously isn’t the point of it. As long as I had my hands on something by Elmore Leonard or Daniel Woodrell, to name just two of my guiding lights, I could survive any airplane flight and every hour-and-a-half wait at the doctor’s. They were masterful storytellers, but they seemed most interested in their characters, the way they thought and moved and talked. God, did they love talk, particularly Leonard, who built book after book on dialogue that carried him to the bestseller list and a place among the best crime novelists ever.

He did not, however, invent noir dialogue. That had been done decades before by Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett and a host of writers now on the verge of being forgotten, people like Cornell Woolrich and Patricia Highsmith and Chester Himes. Then film noir put that brand of smart talk in the mouths of actors who became synonymous with it, from Bogart to Mitchum to Ida Lupino. I’ve always been a sucker for those noir movies out of the late 40s and early 50s where gunmen lurk in the shadows and danger floats in on clouds of cigarette smoke. But what really got me was a moment like the one in Larceny when Shelley Winters, as a con man’s tootsie, tells a potential boy toy, “You kiss like you’re paying off an election bet.” Just as memorable was Yvonne De Carlo playing Burt Lancaster for a sap in Criss Cross. Even when the armored car heist she’s lured him into goes sideways and they know they’re going to die, he’s making cow eyes at her. “I never wanted the money,” he says. “I just wanted you.”

L.A. has always been ripe with stories like those, so perhaps it’s only natural that this native son feels a sense of pride in local sex, treachery, desperation and murder. Film noir may once have fed on such indelicacies, but more and more it belongs to the past no matter how great Chinatown and L.A. Confidential were. It is left to the city’s great contemporary noir writers – Michael Connelly, James Ellroy, Walter Mosley, Richard Lange and all the rest – to make the most of its image as a luscious piece of fruit that has fallen from the tree and lies rotting in the relentless sunshine.

I’m under some of the same influences they are, but I made little use of the city’s underbelly until I started thinking about writing a novel. Now, no matter where I am in L.A., I don’t have to drive far to show you what I’m talking about. I weave along city streets so pocked and neglected they wouldn’t be out of place in the most shell-shocked regions of Syria and Afghanistan. I pass handsome apartment complexes and think of the tricks that got turned in them and the building managers who may have played blind in exchange for sex. I follow reports of the violence that’s always waiting to happen in every corner of the city, secure in the knowledge that it wasn’t O.J. Simpson who proved the famous and near famous can be as bloody as the poor and gang-ridden.

There was once an actor named Tom Neal – the star of the classic cheapo noir Detour – who went into eclipse and ended up working as a landscaper until he put a bullet from a .45 in his estranged wife’s head.

When I hear a story like that, it’s hard to imagine writing anything but noir.

BB: Did you outline the story before you started writing or make it up as you went along?

JS: Before I started writing my novel, I would have told you I needed an outline. How could I possibly work without a net on something so big, right? Outlines were always part of my process in journalism, whether I was on a newspaper deadline and roughed one out in three or four minutes or had a day or two to figure out how to structure a magazine piece. In Hollywood, an outline is practically mandatory in both TV and movie writing because nobody wants to leave anything to chance. There are still storytelling disasters, obviously – I’ve been guilty of more than a few myself – but the people in charge like the idea of having an outline so they can hand it to the next writer if the first one bites the dust.

So did I outline A Better Goodbye?

Hell, no.

I thought of it, of course. But then I started writing, and soon enough I had a plan of attack in my head: I wouldn’t stop until I knew where I was going to pick up the next day. The first thing I’d do when I sat down every morning was to read what I’d written the day before. I’d make changes, sometimes lots of them, but sooner or later I’d move into the new day’s work with a full head of steam.

I had a notion of where I was going all along, but I wanted to keep things flexible so I could change direction or take side trips, like one where Onus DuPree Jr., my prize sociopath, goes pet shopping at a pit bull fight. Likewise, with an outline, I might not have been as willing to introduce a character I hadn’t thought of before. I wanted the book to be picaresque; I wanted readers to meet characters they weren’t expecting when they least expected them. Admittedly, these characters didn’t always advance the story, but they helped draw a picture of the world where A Better Goodbye takes place. Other times, they complicated things. I’m thinking in particular of a highly pissed-off neighbor lady who pops up in the middle of a scene where DuPree and his partner in crime, Scott Crandall, are hunting for Nick Pafko and Jenny Yee, two lost souls who are trying to save themselves. Maybe everything should have been streamlined at this point of the book, but that’s not the way life works, and I didn’t think my story should work that way, either.

BB: Who was the first character you dreamed up?

JS: The fighter, naturally. With me, it’s always the fighter. I guess it’s because I wrote so much boxing when I worked in newspapers. As soon as I came to Hollywood and people learned about my background, they wanted me to write about fighters. I did it for Miami Vice and Midnight Caller, a dramedy called Hooperman, and an aborted attempt to bring back The Untouchables. And I had my own ideas, too. My two best scripts focused on fighters, a TV pilot called The Ring and a screenplay called American Original, which was based on a W.C. Heinz magazine piece about a hard-punching, hard-living little Texan named Lew Jenkins. Neither went anywhere, but that didn’t change my mind about fighters as characters.

The fighter in The Ring was Nick Pafko, a young middleweight out of a blue-collar neighborhood in Chicago, with a father who has a major gambling problem, a stand-up mother who’s ready to leave the old man, a kid brother in and out of trouble with the law, and a big sister who graduated college and yearns to leave the old ’hood behind. It’s not a coincidence that the fighter in A Better Goodbye is also named Nick Pafko. Of course I’ve given him a life far different than the one he would have had if The Ring had made it onto the air and run for five seasons.

That Nick would have become a world champion, married a good woman, fathered a couple of kids, succumbed to temptations that cost him his title, and somehow pieced his life back together as he regained the championship. The Nick in the novel didn’t come close to any of that. He was on his way to realizing his dream when he mortally injured the man he was fighting in what should have been nothing more than a steppingstone bout. You fight an old warhorse, you learn some lessons, and you get out of there with a win. Simple, right? Not when Nick blows up at his opponent’s dirty tricks and the referee freezes. What happens then is tragedy all the way around. No winners, only losers.

Nick tried to fight again after that, but he couldn’t do it. In that regard, he was like a fine young fighter from L.A. named Gabriel Ruelas, who never fought again after killing a man in the ring. I wanted Nick to carry a burden so heavy it made it hard for him to take one step after another. He couldn’t be like Sugar Ray Robinson or Emile Griffith, both of whom fought their way past such impossibly dark moments. Nick is a tough guy and, way down deep, a decent one. He can still make you laugh with a smart-assed remark, and something in him makes it impossible to back down to anyone even when they’re holding a gun. But beneath the emotional camouflage, there is a beaten man. What I tried to do was to tell the story of how he finds his way past that.

BB: Let’s talk about your female protagonist and how you learned about the massage industry. Did this entail you doing the full Gay Talese? Did ya manage a massage parlor?

JS: Fortunately, I never got that desperate when I was doing my research. Of course, when I cold-called some masseuses and said I was a writer who wanted to talk to them about their work, they instantly accused me of trying to get a freebie. Anyone who reads the book will soon realize that these girls get lots of strange requests – maybe exotic is a better word – so their reaction was understandable. But I really did need to talk to them because the massage business was as foreign to me as boxing was familiar.

All I knew about it in the beginning was that it had exploded. From the late 80s up past the millennium, the back pages of L.A. Weekly, the city’s smart and lively alternative newspaper, were jammed with page after page of massage ads. Some took up chunks of a page, with stock photos of pretty girls who had probably never been near a jack shack; others ran just two or three lines. But they all paid to advertise. Even if you’re like me and say jack, queen, king after you get to ten, you knew the Weekly and all the other publications where the sex trade did its advertising were making a pile of money.

Being an old newspaper guy, I thought there was a fascinating story waiting to be written about the massage industry, or maybe a TV station would put on its big boy pants and do a feature that went beyond ratings-week sleaze. It never happened. The only time massage operations got any ink or airtime was when the cops raided them during a local election campaign. There’s nothing safer for a politician to ad his name to than a crusade against sin. Naturally, as soon as the election was over, the pols and cops forgot those obliging ladies existed, and it was back to business as usual.

The growth of the Internet made business even better because now there were photos accompanying a lot of the ads on the rub-and-tug websites. Sometimes the photos were actually of the girls who had taken out the ads – well, either the girls or a prominent part of their anatomy.

And where did they ply their trade? They worked out of apartments that ranged from rancid to really nice as well as guesthouses and sometimes even single-family homes. Some were in neighborhoods that scared off clients who drove Porsches, and others had addresses that automatically made guys who needed their itch scratched think of money and class.

And who did these girls work for? They worked for people who knew their way around the business, veteran pimps and masseuses or straight-up hookers who had set up their own operations. But there were always newcomers like Scott Crandall, the pimp in my novel, who has figured out that his shot at Hollywood stardom is over and he needs to new source of income. It’s bosses like Scott – greedy, venal, always complaining, and way too eager to sample the merchandise – who unwittingly convince girls to go out on their own. Sometimes a girl will have the charisma to take a jack shack’s biggest earners with her when she sets up shop. More likely, she will fly solo so she can set her own schedule and make her own rules and regulations.

That’s what my female protagonist, Jenny Yee, tried to do until she realized that self-discipline wasn’t her strong suit. When we meet her, she’s calling herself Suki – stage names are as important as lingerie in the massage business – and working for a successful realtor with a couple other girls in a well maintained, otherwise tame high-rise in Sherman Oaks. Life is good there until it isn’t, and when it goes bad, it does so in a horrific way. You’d think the trauma would be enough to scare Jenny out of the business for keeps, but when she gets in a jam financially months later, she knows only one way to make money fast – massage. Her primary requirement is that her next stop has security. That’s why she goes to work for Scott, whose hired muscle is Nick Pafko. Now we have our two lost souls together. After that, it’s up to them to connect.

Okay, I hear you. That still doesn’t explain how I could write intimately about Jenny’s life in and out of the sex trade. I needed a masseuse who would tell me her story – the glamorous stuff, the unglamorous stuff, the weird stuff, the funny stuff, the sexy stuff. I mean, I could imagine my share of scenarios, but I really needed verisimilitude. I got it in the most roundabout way.

I knew a young woman who was going to UCLA, very smart, very straight, would sooner run with the bulls at Pamplona than do massage. But when I told her about my idea for a novel and how I was running out of patience in my masseuse who would sit down and talk about her secret life. Right away my friend said, “Oh, I know someone like that.” Did she ever.

My friend’s friend was Asian, bright, and cuter than the law allows. It didn’t take a whole lot of imagination to see why guys with disposable income were beating down her door. She was using the money she made to pay her way to UCLA, and one of the great factoids about her was that she got her first job as a masseuse through an ad in the campus newspaper. Best of all, though, she was a non-stop talker with a gift for anecdote. She spoke in whole paragraphs, not just in sentences. And she was funny, insightful and fully capable of, say, weaving her analysis of Catcher In the Rye in with her take on her clients. Not that she hated her clients – she genuinely liked many of them – but they were giving her an education beyond the one she was getting at UCLA. And she was making the most of it.

I met one other masseuse through my guide to the sex trade, a sweet, quiet Caucasian who blushingly provided me with telling details about things like pigsty bathrooms, over-amorous clients, and creepy security guards. But the second masseuse couldn’t have been more different from the Asian girl; she was shy, relatively inexperienced sexually and, I think, pretty much uncomfortable about touching naked strangers.

The Asian girl, on the other hand, looked at this strange life as a lark that not only paid for her education but bought her drugs and financed trips to Las Vegas and let her carry on at every rave she could get to. While it was all her friend could do to provide a happy ending to a massage, the Asian girl operated by a different set of rules entirely. She wouldn’t have sex with just any guy who walked through the door, the way some girls would. But if she liked someone the way she might if they’d met in a class or at a club, then she was perfectly comfortable getting intimate. A guy like that might come along once or twice a year – all right, maybe three times – but she wouldn’t keep two guys on the string at the same time because she wasn’t a ho. She was simply someone who enjoyed sex when the right guy came along. When you think about it, that didn’t make her much different than women who wouldn’t dream of doing massage. It was just that guys had to pay two hundred dollars to see her the first time, and probably many times after that, before their relationship ceased to be a business transaction.

If I had a daughter who followed the Asian girl’s lead, I’d be mortified, disappointed, crushed. I’d wonder where I went wrong as a parent and how I could convince her to consider a more traditional part-time job. But it wasn’t like she was being exploited by anyone. She had made a choice, and she never encountered anything nearly as horrific as does the character she inspired in my novel. She survived the useless boyfriends and angry husbands that are among the hazards of the trade, and she got her education. Then she walked away from the massage business. I still hear from her once in a while. She says she’s doing well in the real world. I’m not surprised. To tell the truth, I’m proud of her.

BB: Man, it seems as if your bad guy was a ton of fun to write.

JS: Some characters call for your heart and soul. Onus DuPree Jr., on the other hand, was undiluted id, a receptacle for every terrible thought I could conjure up, a tool for every act of violence I could imagine him contemplating. I loved all of my characters – well, maybe not Scott Crandall, who’s a shit weasel – but DuPree filled me with perverse joy.

He seized control of my imagination as soon as I came up with his name: Onus DuPree Jr. Names count for a lot in noir fiction, whether you’re talking about Dashiell Hamett’s Sam Spade or Elmore Leonard’s cold-blooded Bobby Shy. In DuPree’s case, I like to think it was the “junior” at the end of his name that sent him over the edge. He was trouble from the day he was born – his own mother said so – but he didn’t want to wear his old man’s name even if it once counted for something in L.A. He was dead set on making his own reputation. It just turned out that his reputation was as a full-blown sociopath who would settle for scaring the prunes out of someone’s grandma if he couldn’t rob someone or spill their blood.

I’d been carrying a character like DuPree around in my head for, I don’t know, fifteen or twenty years, ever since I read in the about a big-time athlete’s son who got in trouble with the law. He went to prison, and that was the last I heard of him until my agent’s assistant told me he’d played high school basketball with the kid. The kid was more than a superb athlete who excelled at every sport; he was a killing machine in street fights who took delight in really hurting anyone crazy enough to tangle with him.

I thought I’d done all I could with the DuPree character when I sold my novel, but one of my editors at Tyrus Books challenged me to come up with a new scene to introduce him. Originally, he’d been parked on the street behind Chuck Berry’s former home, waiting to rob a drug dealer who made house calls. The new intro is better because it shows DuPree on the move, strolling into a Sunset Strip club, calling someone who approaches him “a faggot,” hitting on another man’s woman, and leaving her boyfriend screaming in pain. That’s DuPree in a nutshell right there: fun, fun, fun.

BB: Well, yes, that brings us back to Scott. Seems to me he’s the one character you didn’t love. Or, let me re-phrase that: He was the one character you seemed to enjoy making an asshole.

JS: It’s not just that Scott is an asshole – it’s how big an asshole he is. He’s Mount Everest. He’s vain, needy, self-deluded, hypocritical, gluttonous, a liar, a sexual predator, and a wannabe bad guy, which may make him more dangerous than a legitimate bad guy like DuPree. And in case you forgot, he’s a pimp. He doesn’t care about anyone or anything except himself. It’s not an uncommon trait among actors, good and bad, but Scott wallows in it even though his career as a B-list TV star is in tatters. He’s ten years past the last decent role he’ll ever get and he’s too lazy to try to reinvent himself. It’s easier just to keep thinking he’s the second coming of Steve McQueen. But the truth is, he’s lucky to be the answer to a trivia question.

Some astute readers may think of Scott as my revenge on a certain backstabbing actor I once worked with. I can’t deny that Scott has a lot in common with that treacherous lug, but he was also inspired by an actor I’ve never met, a guy with a big, uncontrollable mouth and an insatiable appetite for pleasures of the flesh. This Rabelaisian thespian flamed out quickly and disappeared from sight, but wherever he is, I hope he knows that aging TV writers still talk about his exploits when they’re gathered around the campfire at night.

After seeing the way I abuse Scott in the name of art, the natural reaction may be to think I hate actors. Actually, I only hate certain actors. There are others I think the world of and consider myself lucky to have had them bring the words I wrote to life. Gary Cole was the North Star of my favorite TV gig, Midnight Caller, on and off camera, a wonderful actor who set the tone for the entire production with his unfailing professionalism. I didn’t have a happy experience on Reasonable Doubts, but I’d gladly go to war alongside Mark Harmon any time. (But not his co-star, Marlee Matlin, no, not ever.) Jonathan Banks, on Wiseguy, was the first actor I felt I was in tune with; my only regret is that I couldn’t repay him by getting a series we discussed – about a sports writer, no less – on the air so he could star in it. Jim Beaver was just beginning to realize what a fine character actor he could be when we crossed paths on Reasonable Doubts; it’s a thrill to see the great work he’s doing now and a pleasure to still call him a friend. Lest you think I lump all actresses with the aforementioned Ms. Matlin, allow me to pay tribute to the incredible Lucy Lawless, without whom Xena would never – I mean never – have entered the zeitgeist and I would still be out knocking on doors, begging for hack work.

Acting may seem glamorous when people are giving great performances or picking up awards or posing for the cover of Vanity Fair, but the reality is something else entirely. It hit me the first time I saw a casting session, with actors lining the hallway, some sitting, some standing or pacing, waiting for their three minutes in front of the producers, going over their lines and, for all I knew, praying they got the part they were up for because they might not work again all year. The anxiety was palpable, even painful. And I say that knowing they accept it as part of the career they’ve chosen – but, Jesus, seeing people who run the risk of rejection day in, day out really does something to you.

So I confess that even though Scott is a walking, talking sphincter, I couldn’t help feeling sorry when I sent him to a disastrous casting session. He encounters a bigger egomaniac than he is, realizes he doesn’t have a prayer of getting the part, and faces a battery of producers so busy eating lunch they probably wouldn’t bother to call 911 if he set himself on fire. Poor son of a bitch, right? For ten seconds, maybe. Then I went back to hating him. That’s how big an asshole he is.

BB: I think the book has sly humor throughout. The one recurring bit – and I don’t know if this was intentional or not – was that all the major characters seem to get stuck in L.A. traffic at one point or another. I thought that was a very good touch and very Angeleno.

JS: You just won yourself all the In-N-Out burgers you can eat. You found some humor in the book. I knew I put it there somewhere. At least I thought I did until I read my first reviews (one pro, one con) and saw that they both regarded the book as humorless. How, I wondered, could they say something like that if they paid any attention at all to the goofy thoughts that run through Scott’s head? Or to some of the tales the girls tell about their clients’ predilections? (The one involving chocolate cream pies still cracks me up every time I think about it.) Most of all, how could they miss the jokes about traffic? Traffic is the funniest thing in L.A. unless you’re stuck in it, and then the joke is on you, sucker.

The only time DuPree seems truly powerless is when he’s on his way to the showdown and he gets stuck on Olympic Boulevard at rush hour. And what does he do then? He starts thinking about what a great cross street Olympic was before all these cars started clogging it up. When he was a kid, you could take it to Westwood from downtown in something like twenty minutes. It’s the kind of thing you expect a stockbroker or a UPS driver to be thinking about. You don’t expect it from a prison-certified prince of darkness. But that’s life in L.A. Even sociopaths have to make concessions when they get behind the wheel.

BB: There are a lot of details – restaurants, bars, stores – that are specific to L.A. Did you consciously try to root your story in time and place?

JS: Your question takes me back to all the Southern writers I’ve read and admired – not just Faulkner and Flannery O’Connor and Eudora Welty, but the wonderful artists they passed the torch to, like Ron Rash, Tom Franklin, Clyde Edgerton, and those departed giants Larry Brown and Harry Crews. They wrote with a sense of place that made you see the kudzu enveloping whole houses, and smell the moonshine cooking, and hear Hank Williams and Bill Monroe on the Opry as you bounced down a rutted road in your daddy’s pick-up truck.

My life never generated anything quite like that, even when I was chasing down stories about cops and politicians and local characters as a general assignment reporter at the Baltimore Evening Sun. But Baltimore was as close as I came to understanding a city because I was out in one neighborhood or another almost every day, seeing how people lived and listening to how they talked and trying to get their stories down right. When I wrote about sports in Washington, D.C., Chicago and Philadelphia, I never had a chance to know them as well. I went to the ballparks, stadiums, arenas and gyms, and I went to the airports, and that was about it. I had a much higher profile than I’d had in Baltimore, but my experiences were limited to a finite number of venues.

By the time I returned to Los Angeles in 1986 – I was born here and left when I was thirteen – I was too busy trying to make the transition to screenwriting to worry about a sense of place. But I was still writing short essays for GQ about anything that came to mind, and my subjects tended to be local, like the city’s greasy spoons, the kind of shoes male Angelenos do and don’t wear, and McCabe’s Guitar Shop, where I both took lessons and saw everyone from Doc Watson to the young Lucinda Williams perform. So one day someone told me he liked the way I write about L.A. and it brought me up short. Do I write about L.A.? Well, yes, I guess I do.

I may have found my own sense of place unwittingly, and it may not be as vivid or deeply felt as that which Southerners possess, but at least it exists. In writing A Better Goodbye, I wanted to paint as vivid a picture as possible of the neighborhoods where the story took us even though I occasionally took liberties with place names. There is, for instance, no Paisano Groceries, where Nick gets held up in the parking lot, nor is every Latino name on Highland Park’s main drag accurate. But when the story shifted to downtown, I didn’t tinker with the name of the Pantry, L.A.’s legendary twenty-four-hour-a-day steak house. Why jump between the real and the imagined? Let’s call it poetic license. It sounds so much nicer than creative indecision.

The year I chose was 2003 because we were still feeling the reverberations of 9/11. It’s one of the reasons Nick gets laid off as a baggage handler at LAX, and he’s soon behind on his rent and desperate to keep a roof over his head. He lives on Beloit Avenue, which was then on the other side of a tumbledown wire fence from the 405 Freeway and was then a stretch of modest apartment buildings. Perhaps the most modest of all was the oleander-shrouded hovel where I lodged Nick in a shoebox one-bedroom apartment. Today, if you drive on Beloit, you’ll see handsome new apartment buildings on one side of the street and a tall brick wall to muffle the freeway noise on the other.

A different version of gentrification has come to Highland Park. In the days I’m writing about, there were still warring street gangs there and the neighborhood was considered, rightly, a blue-collar Latino stronghold. Back then, only young couples long on pioneer spirit rolled the dice and bought old homes in need of renovation. Now it’s L.A.’s new hot neighborhood and every day is a symphony featuring hammers and power saws. Everyone calls it progress except the residents who were displaced.

BB: You can see Elmore Leonard’s influence in this book. Was that something you were aware of when you were writing it?

JS: Every writer is a product of his influences. You take your life experiences and all the novels, short stories and, in my case, great journalism you have read and admired, and you throw everything in a blender and see what kind of a mess you have. Then you start weeding out the things that don’t work for you, and you begin saying things your way. Sooner or later your voice emerges. In Leonard’s case, I’m sure he read Zane Gray, Louis L’Amour and Max Short before he started writing Western novels in his own particular way. When he turned to crime fiction, his influences were as varied as George V. Higgins, whose novels were borne by pitch-perfect hard-guy dialogue, and the legendary sports writer W.C. Heinz and the otherwise forgotten Richard Bissell.

What I tried to guard against in A Better Goodbye was mimicking Leonard’s writing style. He can be very seductive that way. If you read his books closely, you’ll see that he constructed his sentences so distinctively that only a fool would try to imitate him. Diagram one sometime – you’ll see what I mean. Where Leonard’s influence does show the most, I think, is in the way I set up the story, with Nick and Jenny trying to outwit DuPree and Scott and none of them being what I’d call brilliant, even Jenny, whose smarts come from books, not the streets or the thug life. And, of course, Onus DuPree Jr.’s name is most definitely an homage to Leonard, whose cool bad guys always had a cool monicker.

But the story I told is much darker than what Leonard made his specialty. There was usually an almost genial quality to a lot of his crime novels; if his characters weren’t in on the joke, then the joke was on them. Scott, the actor turned pimp, is the only character in my novel who gets that kind of treatment. Leonard, on the other hand, could fill a book with characters like him. It’s one of about a million reasons why Leonard’s crime novels went down so smoothly. There is, for example, a moment in Unknown Man #89, which is one of my favorites, when the chief villain tells his henchman to throw some poor sap out a hotel-room window. The henchman says something like, “How far down you want him to go?” And the villain says, “Oh, all the way. Might as well.” That’s quintessential Leonard – I laugh every time I think of it.

A Better Goodbye became truly my own when I diverged from his influence by making Nick more haunted and complicated that any Leonard hero I can recall. I wasn’t writing a mystery; I was doing a character piece that hewed as close to literary fiction as it did to noir. To light my path, I turned to James Crumley’s The Last Good Kiss and any number of James Lee Burke’s crime novels. But most of all, there was Fat City, Leonard Gardner’s classic boxing novel Fat City. Gardner’s characters existed in a bleak, unforgiving world, and that was the kind of world I wanted to inflict on Nick and Jenny. They were lost souls just trying to live another day in a city that chews up people like them.

Life is rarely that flinty and elemental for Elmore Leonard’s characters; they’re too busy trying to scam each other. My characters don’t know the meaning of scam; they’re forced to confront whatever life throws at them no matter how grave a danger they face. Like Nick says when someone threatens to kill him: “What if I told you don’t care?”

BB: You once told me that when you’re writing for the screen, you want to get into a scene as late as possible and get out as soon as possible, to get right to the heart of the action. Did you use the same approach with your novel?

JS: I think novels call for a different approach, at least some of the time. On the screen, whether you’re writing a one-hour episode of TV or a two-and-a-half hour movie, time is of the essence. As audiences have become increasingly sophisticated, writers don’t need to fool around with, say, an airplane landing in New York to show that the hero is there now. More important, screenwriting has become increasingly elliptical. Just think of all the scenes in The Wire that were probably only a half-page long, with maybe a line or two of dialogue, and yet they were as beautifully written as they were economical.

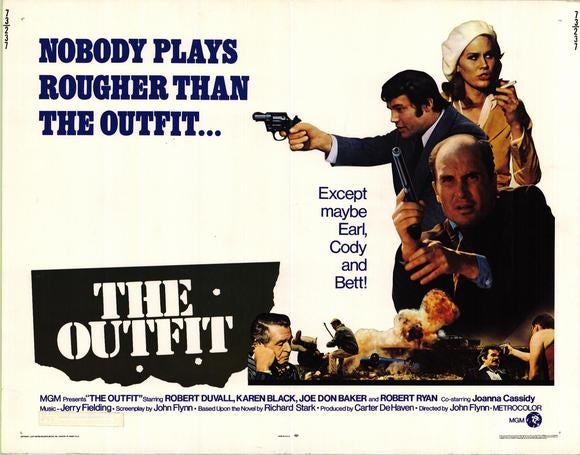

Novels are a different proposition, or so it seems to me as both a first-time novelist and an unschooled one. All I really know about novels is that I wrote one and was fortunate enough to get it published. Having had that experience, I reveled in the luxury of time that novels provide. Or maybe it’s the illusion of time. Whatever, you’re not writing in the middle of the page the way you are with a screenplay. You’re writing margin to margin, which gives you room to explore the inner life of characters. You can have a character driving to a conference on gun control while he’s thinking about an incident with a gun he was involved in twenty years earlier. You don’t have the same ability to jump around in time that way in screenwriting unless you do a flashback, and flashbacks weren’t considered cool when I worked in Hollywood. Neither, in a lot of cases, was backstory. People were always lavishing praise on movies where the characters had no backstory to speak of. It was an approach that could work brilliantly on the screen (Eastwood’s Spaghetti Westerns), and sometimes on the page, too (the Parker novels that Donald Westlake wrote as Richard Stark). But I still prefer the idea of finding out something about the characters I’m being asked to invest in emotionally.

In A Better Goodbye, Nick, Jenny, Scott and DuPree all come at the reader in roundabout fashion. Each of them has an introductory chapter that lets us know who they are and what they’re about. I hope I didn’t abuse the privilege, but I wanted them to have room to breathe. It was an approach I went back to again and again over the course of the book. But I changed pace in other scenes, making them short and punchy because that added to their impact and kept the story moving. That’s where the point of entry in a scene comes into play. You start at the top and start whittling away what Elmore Leonard called the things nobody reads. Once they’re out of the way, you can get down to what the scene is about.

BB: So, a noir for your first novel begs the natural follow-up question: What’s next?

JS: Another novel. I want to see if lightning can strike the same writer twice. But my next one won’t be noir or anything close to it. The setting is Los Angeles once again, but this time it will be the L.A. where I spent my childhood in the late 1940s and early 50s. The story is about someone who lived a fascinating life without realizing it until it was behind him. I’ve been thinking about this one for the past few years, trying to figure out a structure to hang things on, and I think I’ve finally come up with something that works. Lately I’ve started hearing my characters talk, and I’d like to know them better. The only way to do that is to write. So, if you’ll excuse me…

[Photo Credit: Painting of woman with cigar by Brian Viveros; rubbersquare; Bags]