Yanks signed Neil Walker on Monday afternoon; late of the Pirates, Mets and most recently Milwaukee, on a 1-year/$4 mil deal to ostensibly be the start at second on Opening Day, but more likely to act as the veteran bridge for both Miguel Andujar and Gleyber Torres. While Walker is essentially a downgrade offensively from Starlin Castro, his defense is considered a valuable upgrade; the hope being that he can stabilize both the right side of the infield and the bottom of the lineup while the Andujar and Torres are being groomed for third and second, respectively (and it doesn’t hurt for the organization that it adds another year of control for both of them). Everyone and their moms knew that Cashman was not going to go straight in with the rookies to start the season, so he played the market and got a solid player for a bargain.

Yanks signed Neil Walker on Monday afternoon; late of the Pirates, Mets and most recently Milwaukee, on a 1-year/$4 mil deal to ostensibly be the start at second on Opening Day, but more likely to act as the veteran bridge for both Miguel Andujar and Gleyber Torres. While Walker is essentially a downgrade offensively from Starlin Castro, his defense is considered a valuable upgrade; the hope being that he can stabilize both the right side of the infield and the bottom of the lineup while the Andujar and Torres are being groomed for third and second, respectively (and it doesn’t hurt for the organization that it adds another year of control for both of them). Everyone and their moms knew that Cashman was not going to go straight in with the rookies to start the season, so he played the market and got a solid player for a bargain.

That sort of selectivity didn’t come from just anywhere; Cashman had started his Yankee career as an intern in the 80s and received an education on how Steinbrenner and the Yanks did business; having a front row to the highs and lows of the organization from the field to the front office. Steinbrenner introduced a young Cashman to his lieutenants by saying, “pay attention; he’s going to be your boss someday.”

In 1995, The Strike continued on into the beginning of April. The players, who didn’t trust the team owners for a minute after they’d forced Commissioner Fay Vincent to resign in 1992 and never bothered to officially replace him, were purportedly striking to prevent the institution of a salary cap planned by the owners, who complained that revenues were down all over and threatened to bankrupt small market teams that didn’t have the capacity of big market teams to be profitable on their own. Revenue sharing was part of their plan, but holding costs down by instituting a cap was preferred. Naturally, this didn’t go over well, and the players’ union sued after walking out. The owners decided to use “replacement” players; mainly baseball players from the minors or independent leagues who would likely not have made it to the bigs at any rate. Striking players discouraged so-called replacement players from considering crossing their picket for the most part, but there were eventually enough players to field teams for each organization to kick-start the new season (though there was not much excitement and a lot of resentment from both players and fans for such a move). Fortunately for baseball (in the long run), an injunction was issued against the owners (by Bronx-bred Judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York Sonia Sotomayor; aka future Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court), forcing them to meet the players and work out a deal while still abiding by the previous expired CBA. By April 2, the strike was over and baseball plotted for a shortened season.

In 1995, The Boss was Steinbrenner once again; having been reinstated in 1993, but remaining low-key as his son-in-law Joe Molloy kept things in order and supported Michael and Showalter as they rebuilt the team from the ground up. Molloy invested in scouting and development; something that had been taken seriously for granted during Steinbrenner’s blustery and blundering run through the 80s. Molloy remained a general partner after George’s return. Within a few years, however, he would leave the organization and the Steinbrenner family mainly due to George’s “managing style”.

In 1995, Buck Showalter would lead the Yankees into the postseason as the first wildcard team in the AL for the new playoff format, but would lose in heartbreaking fashion to a stacked Seattle Mariners team which boasted future Hall of Famers, team favorites as well as former and future Yankees. Steinbrenner, once again being Steinbrenner, wanted among other things a blood sacrifice for this “failure” in Rick Down, Buck’s hitting coach, during negotiations for an extension. Buck, figuring this was part of the negotiations, replied no, I can’t accept a contract under those circumstances, and waited for a reply. The reply came from his wife, who informed him that reporters were calling to get his response after being let go. Buck and George had been butting heads for some time, with George again doing what he normally did in taking potshots at players or making veiled threats against the coaching staff. Buck, by most accounts not an easy man to get along with himself, pushed back against the onslaught, the tension permeating the Stadium and the clubhouse. Whether or not you can blame Buck for not keeping his players loose or George for disrupting the peace that had settled in his absence, Steinbrenner took advantage of the rejection to cut ties with Showalter altogether. The burn would last seemingly forever.

In 1995, on August 13 at 2am, the legendary and uncompromisingly American Mickey Mantle left our world. Flags were hung in half mast and bittersweet tears were shed across the Yankee universe as people of all thoughts who knew what a baseball was for reflected on all of what made him The Mick.

Donnie Baseball finally made it to the postseason, which had sadly eluded him throughout his career. He acquitted himself well; going 10 for 24 with a .417/.440./708 slash line; four doubles, six ribbies and a homer in Game 2. All the more heartbreaking, Mattingly played like a man rediscovering his lost childhood and trying to reach heaven; the fans willing him along every step of the way. The stadium conducted the electricity of excitement and relief, as well as the cold gusts of desperation. Mattingly wanted it. The fans wanted. The team wanted it. The whole city wanted it. But the Mariners, led by a strong mix of youth and veteran grit that included Randy Johnson, Ken Griffey, Jr. Edgar Martinez, Jay Buhner, Tino Martinez and phenom shortstop Alex Rodriguez, outlasted the dream.

Stick, for reasons I don’t really know of at the moment, yet at an oddly appropriate moment, resigned as general manager at the end of the season and took on the mantle of Vice President of Scouting with the team. Despite the playoff loss, the Yankees were set up for a marathon run. Along with Molloy, he made two crucial recommendations for the next hires…

- Opening Day Starters: underline

- Also Played: #

- Regulars On Roster: blank

- Renowned From Other Teams: bold

- Unheralded Rookie/Prospect: *

- Unheralded Vet: italics

- Rookie Season (became regulars): ~

1995 New York Yankees Roster

Pitchers

- 54 Joe Ausanio

- 25 Scott Bankhead

- 31 Brian Boehringer*

- 36 David Cone

- 47 Dave Eiland

- 41 Sterling Hitchcock

- 47 Rick Honeycutt

- 57 Steve Howe#

- 28 Scott Kamieniecki

- 22 Jimmy Key

- 34 Rob MacDonald

- 38 Josías Manzanillo

- 19 Jack McDowell

- 39 Jeff Patterson*

- 56 Dave Pavlas

- 33 Mélido Pérez

- 46 Andy Pettitte~

- 42 Mariano Rivera~

- 35 John Wetteland#

- 27 Bob Wickman#

Catchers

- 13 Jim Leyritz

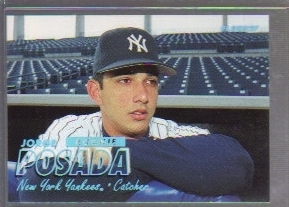

- 62 Jorge Posada~

- 20 Mike Stanley

Infielders

- 12 Wade Boggs

- 24 Russ Davis

- 50 Robert Eenhoorn

- 26 Kevin Elster

- 6 Tony Fernández

- 2 Derek Jeter~

- 14 Pat Kelly

- 23 Don Mattingly

- 43 Dave Silvestri

- 18 Randy Velarde

Outfielders

- 39 Dion James

- 21 Paul O’Neill

- 17 Luis Polonia

- 17, 25 Rubén Rivera+

- 26 Darryl Strawberry

- 45 Danny Tartabull

- 51 Bernie Williams

- 29 Gerald Williams#

Offseason

- December 14, 1994: Jack McDowell was traded by the Chicago White Sox to the New York Yankees for a player to be named later and Keith Heberling (minors). The New York Yankees sent Lyle Mouton (April 22, 1995) to the White Sox to complete the trade.

- December 15, 1994:Tony Fernández was signed as a Free Agent with the New York Yankees.

Transactions

- April 12, 1995: Randy Velarde was signed as a Free Agent with the New York Yankees.

- June 5, 1995: Josías Manzanillo was selected off waivers by the New York Yankees from the New York Mets.

- June 8, 1995: Kevin Elster was released by the New York Yankees.

- June 19, 1995: Darryl Strawberry was signed as a Free Agent with the New York Yankees.

- July 1, 1995: Kevin Maas was signed as a Free Agent with the New York Yankees.

- July 16, 1995: Dave Silvestri was traded by the New York Yankees to the Montreal Expos for Tyrone Horne (minors).

- July 28, 1995: David Cone was traded by the Toronto Blue Jays to the New York Yankees for Marty Janzen, Jason Jarvis (minors), and Mike Gordon (minors).

- July 28, 1995: Danny Tartabull was traded by the New York Yankees to the Oakland Athletics for Rubén Sierra and Jason Beverlin.

- August 11, 1995: Luis Polonia was traded by the New York Yankees to the Atlanta Braves for Troy Hughes (minors).

Draft picks

June 1, 1995: Donzell McDonald was drafted by the New York Yankees in the 22nd round of the 1995 amateur draft. Player signed July 22, 1995.

June 1, 1995: Future NFL quarterback Daunte Culpepper was drafted by the New York Yankees in the 26th round (730th pick) of the 1995 amateur draft. Culpepper was drafted out of Vanguard High School.

Dante Culpepper… the Yanks sure love their foosball QBs (they just had one in for a week or two of Spring Training, didn’t they?). Danny Tartabull, who had become a frequent target of Steinbrenner, was traded for the indomitable Ruben Sierra, who somehow managed to miss a championship with the Yanks in two tours with the team. Polonia was traded away for a minor leaguer who never made it to the bigs. David Cone finally did make it to the Yanks though, after several years of trying to get him. Kevin Maas made a cameo appearance on a minor league contract, but did not play for the big club, soon moving onto Milwaukee’s minors and then Japan. How many knew or remember that Strawberry actually had two separate stints with the Yanks? Though not separated by much, Darryl first signed with the Yanks mid-season in 1995 after having been suspended for drug use (cocaine, an old-fashioned drug suspension by today’s standards). However, he started out in 1996 with the indie St. Paul Saints, mainly to clean himself up and get into real baseball shape. The Yanks resigned him on July 4, 1996 and the rest is written about in many biographies of him, other players and of the Yankee Dynasty.

Octavio Antonio Fernández Castro; better known as Tony Fernandez. A stalwart of the Toronto Blue Jays from the early 80s-on (though he only played and won with the Jays in the second of their back-to-back championships due to having been traded to San Diego a few seasons earlier, then traded from the Mets back to Toronto in mid-season), he was considered one of the premier shortstops in baseball for a combination of clutch hitting and sparkling defense earlier in his career, but then his prolific production stalled by the early 90s and he never managed to reach the pinnacle of personal stardom; he was one of three young shortstops in 1983 predicted to be a sure-shot Hall of Famer; the other two being Alan Trammel and Cal Ripkin, Jr., whom all played together in the All Star Game in 1987. However, in these parts Tony is known best for getting injured in May of 1995, which opened the door for another shortstop who ended up sticking around for a good while. Oh, he did have some heroic moments, like in 1997 when he hit a home run off of Orioles reliever Armando Benitez to clinch the pennant for Cleveland, and he did contribute a lot to Toronto winning their second championship in a row, and he even helped them win their first division title way back when. But because his career stats didn’t add up to dominant player status, the damned voters dropped him off the ballot after his first try in 2007.

John Wetteland, old reliable, was traded to the Yanks from Montreal for a player with a last name that you probably have to pause before saying and an interesting career of his own. Wetteland had originally been drafted by the Mets in 1984, but he turned them down and was drafted by the Dodgers a year later. In December 1987, he was a Rule 5 selection by the Detroit Tigers, but was later returned. In 1991, he was involved in the trade that brought Reds All-Star Eric Davis to L.A. to be united with his homeboy Strawberry. He was subsequently flipped with someone else to the Expos for Dave Martinez, Willie Greene and somebody else, where he finally established himself as a star reliever. Stick closed in on that promise and swung an easy deal, one that greatly benefitted them in the long run. However, Wetteland’s stay with the Yankees was relatively short compared to other places; his longest tenure being with the Texas Rangers, with whom he signed as a free agent for the first time in his career; a move that shocked and likely annoyed him at the time, but worked out again for the Yankees in the long run.

For some reason, I remember Scott Bankhead’s name, though not him as a player so much. He was a first round draft pick by the Kansas City Royals in 1984 and quickly debuted for them in 1986, but ended up being part of a trade that brought Danny Tartabull to the Royals from Seattle. The bulk of his career was with the Mariners from then until 1991, when injuries diminished his pitching ability and he was eventually released. He reinvented himself as a reliever and played for Boston until his contract was bought by the Yanks in 1994, but the strike prevented him from playing. When he did, it was basically a one-and-done deal; barely used and barely missed. Rick Honeycutt I remember from the Oakland A’s of the late 80’s with their dominant pitching, from starters to relievers. Honeycutt probably represents the last of the Mohicans in that respect; the remaining player from that particular championship team either poached or signed on the cheap in their late career stage by the Yanks, this time for a postseason push in late September. He didn’t help much, and ended up with the Cardinals the following season, finishing out his long career with them a year later.

And then there’s “Black Jack” McDowell. Sigh. He was actually pretty good for the Yanks in his lone season, but the infamous “Jack Ass” incident when he walked off the mound after being bombed out by his former team to a cascade of boos and subsequently giving the fans a defiant finger not only torpedoed whatever good will might have existed for him to that point, but effectively put a hex on his career from then on. It was McDowell who gave up the wild card series-winning hit to Mariners hero Edgar Martinez in Game 5 that year, and it was he who Steinbrenner derided the most at every opportunity he got. Luckily for him, he was a free agent at the end of the season and he signed with Cleveland, who was another team on the come-up, but he had lost his mojo by that point and retired four years later after being released by Anaheim. At least he had his music to fall back on, though it’s been said that it was a night of drinking with his musician buddies that led to the Jack Ass incident.

Lastly, before I forget, the + after Ruben Rivera; cousin of the legend with the same name. This Rivera was the almost exact opposite of his cousin; highly anticipated to be a prolific outfielder with all kinds of tools, he made little impression on the Yankees in his first two seasons beyond being highly promising, but highly immature and was traded in 1997 season to San Diego, where he played the bulk of his major league career. But even as a starter, he was a poor hitter and was subsequently released by the Padres. After two seasons of failing as a role player for Cincinnati and Texas, he was once again signed by the Yanks, largely on the strength of his cousin.

So what does he do? Steal Jeter’s glove and bat and sell them for $2,500. What is worse, honestly: that he stole his teammate’s work tools, or that he sold them so cheaply? His teammates voted him off the team, and the front office followed suit and released him. He made one last ditch effort to salvage his MLB career with San Francisco, but it just didn’t work. After a couple years in team minors, he ended up making his way to Mexico, where he was ironically able to put together a highly respectable career, and at age 44 (though it was erroneously announced that he’d retired as a player in 2015), he is still playing pro ball. All of which is to say: nepotism guarantees nothing more than an opportunity most people have to fight hard to get, if they get it at all. But in baseball, there always seems to be some form of redemption.